In Spotify’s world, the narratives of music are defined by false equivalencies, as streaming services scramble to assert their own value. Music streaming services declare that they’re saving the industry (!) due to the fact that total music industry profits have risen in the streaming era, the first music industry increases in years. But more gross revenue does not equate to an industry where the vast majority of artists are able to make a living. They claim to be “leveling the playing field” for artists to access fans. But just because these tools are literally accessible to the majority of artists does not mean that all artists have a fair shot at making these tools work for them—as we learned a couple of years ago, 99% of the streams on Spotify go to only 10% of artists on the platform. And just because someone is literally listening to a greater number of artists via their Discover Weekly playlists doesn’t mean they are processing or retaining any names of artists included therein, undermining the suggestion that algorithmic playlists lead to more adventurous discovery. In a changing industry, the numbers can be deceptive.

Somewhere between Drake’s 2016 really-long-player Views and last year’s one-hour-and-forty-six minute Migos record Culture II, another narrative emerged, as nearly every major music outlet rushed to read into the expanding length of albums. AV Club dubs ours “the era of the way-too-long album,” while The Guardian wonders if musicians are “spreading themselves too thinly.” Pitchfork wants to know, “Are Rap Albums Really Getting Longer?” Fact put it more directly in 2016, declaring that “albums are getting unbearably long…and bullshit new streaming rules are to blame.”

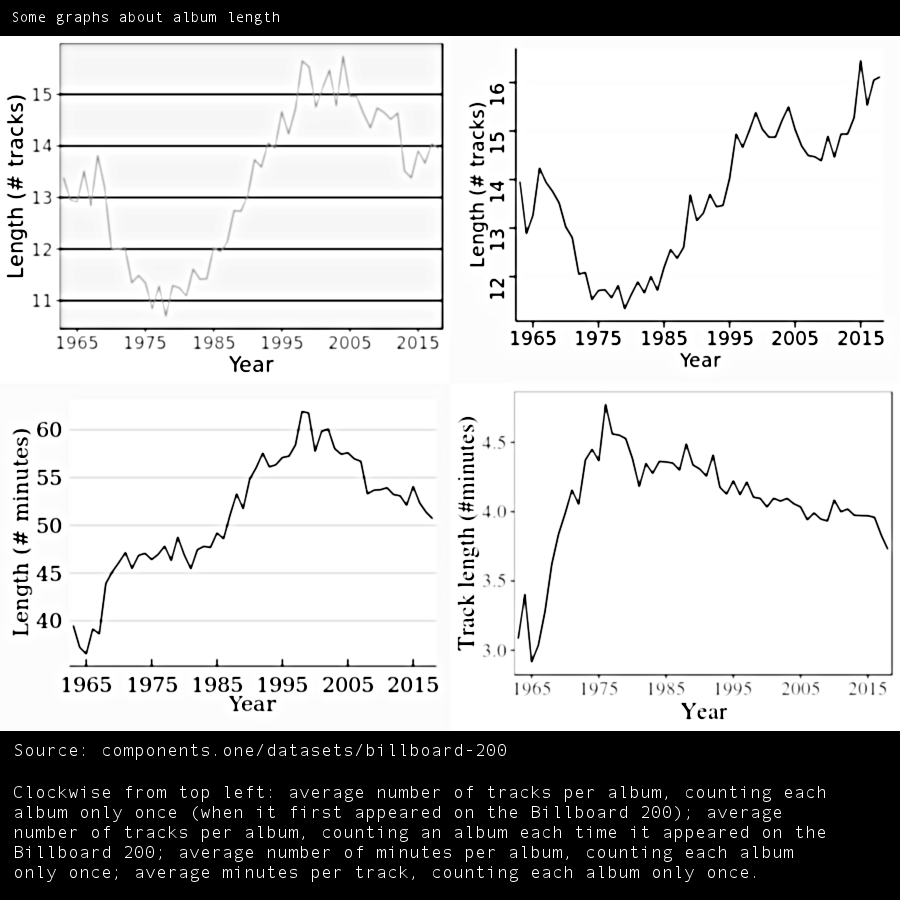

But is this an actual phenomenon, or a trend over-inflated by a few high-profile outliers? Are albums lengths generally increasing, or is it that a small number of extremely visible super-long albums, with the backing of the major-label machine, are giving us the impression of such? Is it just a myth perpetuated by Drake albums?

Yes and no; maybe both. It’s unclear whether any one change is part of a drastic trend, a subtle shift, or a blip entirely. The longest number-one albums between 2011 and 2018 all fall within the last of the two years, but the extent to which the aggregate has followed suit depends on granular technicalities: Count an album every time it appeared in the Billboard 200, no matter how many times it charted, and album length is climbing with the steepness of a mortgage-bubble. Remove duplicate albums and what’s left is maybe a brief aberration in an otherwise sinusoidal flow.

In reality, the ultra-long album is one of many trends major-labels are betting on in the streaming era, but it’s one that has become popular among a handful of big-name artists. There are still plenty of pop albums reaching success on the charts without 20+ tracks; the “era of the way-too-long album” is hardly absolute. But even so, the decisions of, say, the Ed Sheerans of the world (whose 16-track album ÷ is frequently cited in these conversations) have outsized consequences for culture. While their ultra-long albums shouldn’t necessarily be seen as a sure sign of the future, they also shouldn’t be ignored.

Another one of the music press’s takes on the phenomenon of the ultra-long album is that this a way artists are “gaming” the streaming services to serve their own bottom lines and scrape together more fractions of cents—particularly since 2014, the year that Billboard charts began to incorporate a metric known as the album-equivalent unit, wherein one album sale equals 10 songs downloads (like through the iTunes store) and also equals 1500 streams. But as with other exploitative digital tools that create more value for themselves than anyone else, we need to ask: are artists gaming the system, or is the system gaming artists?

The answer is probably somewhere in the middle, with as much blame to be placed on the services as on disoriented major-label execs who are likely encouraging albums of a certain length (or maybe even contractually requiring it) as they observe the successes of artists like Drake and Ed Sheeran, who have both ended up as the most-streamed artists on Spotify at year-end time every year since the dawn of the album-equivalent unit: Sheeran in 2014, Drake in 2015, Drake again in 2016, Sheeran again in 2017, Drake again in 2018. There is certainly a connection between their absurdly long track lists.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with an extremely long album, and pushing back against it entirely might be just as arbitrary—who can really say what length will serve what artist?—but it’s hard to ignore the way it fits into a bigger shift of music discovery and listening trends towards playlists meant to be left in the background, an environment where connections with playlists and curators are favored over connections with songs or albums. What does it mean for artists to use their albums to contribute to those shifting dynamics? In a sense it all just feels like part of the grand shift from album-listening to playlist-listening (perhaps most clearly seen when Drake actually released More Life as a playlist rather than an album), but where artists are more or less using their own albums to contribute to the obsolescence of albums. —Liz Pelly

Analysis by Andrew Thompson, moving image by Heather Mease