Summary

This report argues that consumer technology reviewers have failed their basic nominal purpose of critiquing tools. Instead, inspired by values introduced by Apple in the late 1990s, the tech review industry prioritizes aesthetic lust as the primary critical factor for evaluating objects. The reification of these values in their scoring system is transmitted to consumers and manufacturers alike. Like other prurient things, the objects designed within this paradigm are optimized not for usefulness but for photogenic and telegenic properties, a framework that finds its fullest realization in YouTube reviews and unboxing videos. There, even the intimation of critical rigor within tech reviewing vanishes, the smartphone becomes the center of gravity, and manufacturers are even further incentivized to design products for end consumers who are less users than viewers.

Introduction

Components has published analyses of critic reviews twice in the past: first about Pitchfork, and later about film and television critics. Both were driven by the challenge to reverse engineer values coded inside the numerical scores assigned by reviewers, and both worked off a premise that such critics probably shouldn't be assigning scores to art in the first place. The stakes for both analyses, though, were quite low. The dwarfed influence of critics has spawned countless reflections (mostly by critics themselves) that ponder their diminishing relevance in an age of user reviews and unlimited content, where the economic costs of listening to or watching something are almost nonexistent.

Product reviews, including the consumer technology reviews analyzed here, are different. The perspectives of sources like PCMag and influencers like Mrwhosetheboss are simultaneously widely sought after and unavoidable. Tech reviews are not produced for consumption with Sunday morning coffee. Rather, each outlet and channel obsessively optimizes every detail of their output — their text, their titles, their HTML, their metadata, all of it — to surface ever higher in the search rankings consumers encounter when they perform their inevitable pre-purchase research. "The epicenter of consumer-driven marketing is the Internet, crucial during the active-evaluation phase as consumers seek information, reviews, and recommendations," writes the management consultancy McKinsey. The tech review sits comfortably in a McKinsey-conceived economic schema in a way a Midsommar review never could. No one at CNET is lamenting the death of the critic.

In 2016, the Pew Research Center conducted a study on e-commerce in the United States, including the importance of online reviews, which included both professional and user reviews. On all three separate measures examined — making consumers feel confident about their purchases, holding companies accountable, and ensuring product safety — respondents overwhelmingly expressed more trust in reviewers than government regulators.

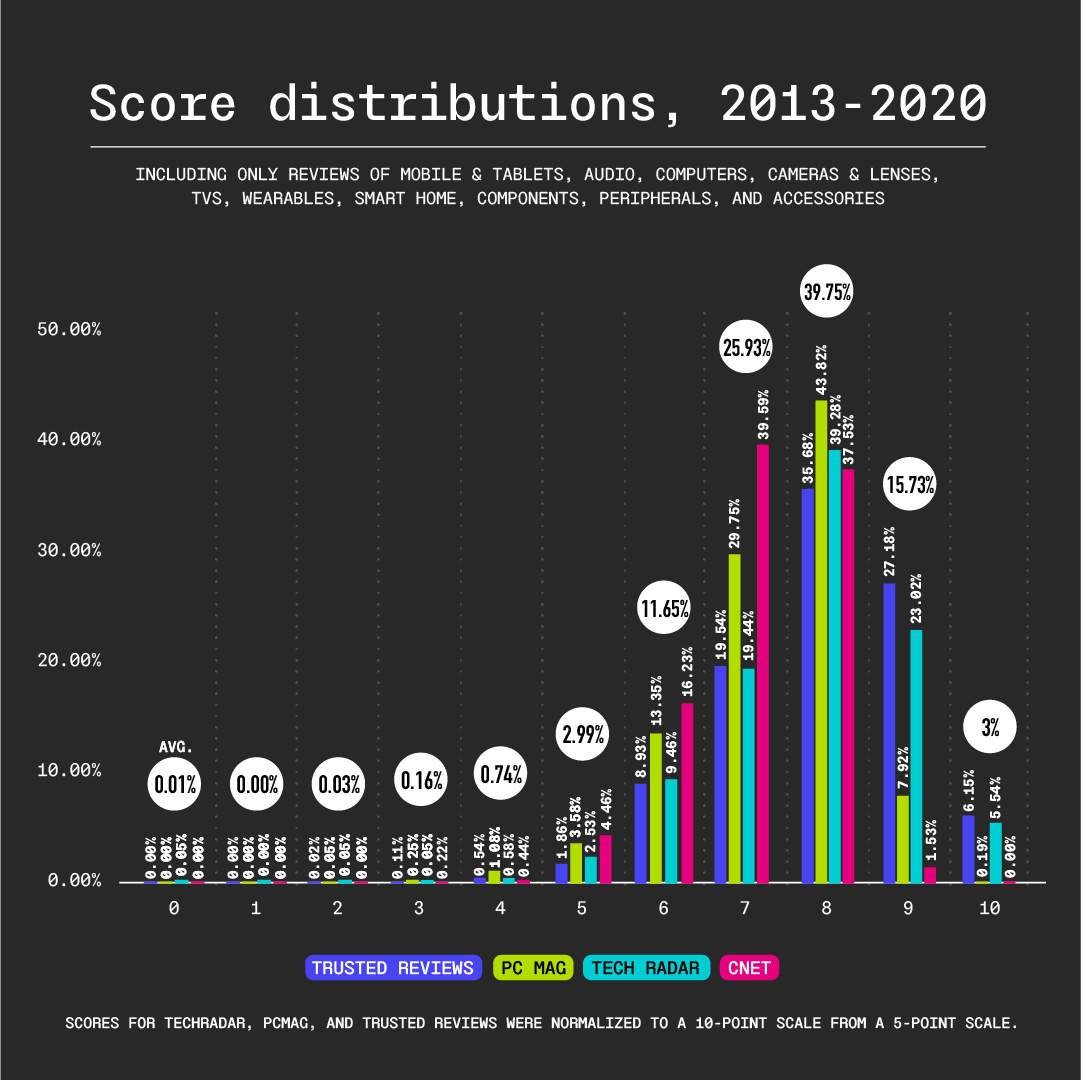

Tech reviewers operate on a premise that nearly every object is a recommended purchase: A majority of reviews

In other words, a random product has better than even odds of receiving a strong recommendation by a tech reviewer, and nearly 9 out of 10 products are considered well within the threshold of purchasability. A reader who happens upon a review in the course of their research will more often than not receive a critical green light.

There are two notable datapoints at the extreme ends of the axis.

First, no product from CNET, PCMag or Trusted Reviews received a score of 0, and at TechRadar, the number of 0-scoring reviews was so low as to be statistical noise.

Second, no score among CNET reviews was ever assigned a 10, and at PCMag, products that earned superlative scores amounted to less than two-tenths of one percent. At TechRadar and Trusted Reviews, the percentage of 10-scoring reviews was about 5.5 percent and 6.1 percent, respectively. In aggregate, only 3 percent of products receive perfect scores.

Taken together, the two datapoints illustrate how this paradigm struggles with concepts of worthlessness or perfection. In fact, the world is more populated by worthless and perfect products than pretty good or even great ones. Hammers, coffee mugs, umbrellas — these objects either work or they don't. If they do, they're effectively perfect. If they don't, they're worthless. This is not to preclude objects from improving over time as ideas, technologies, and standards change, and for the meaning of perfection or worthlessness to shift. But tech reviews, as we'll see in more detail later, rest on a belief that they must improve, and that the exact function an object is supposed to serve is never all that clear. At the same time, because that purpose is not clear, it means the object can never measurably fail to fulfill it.

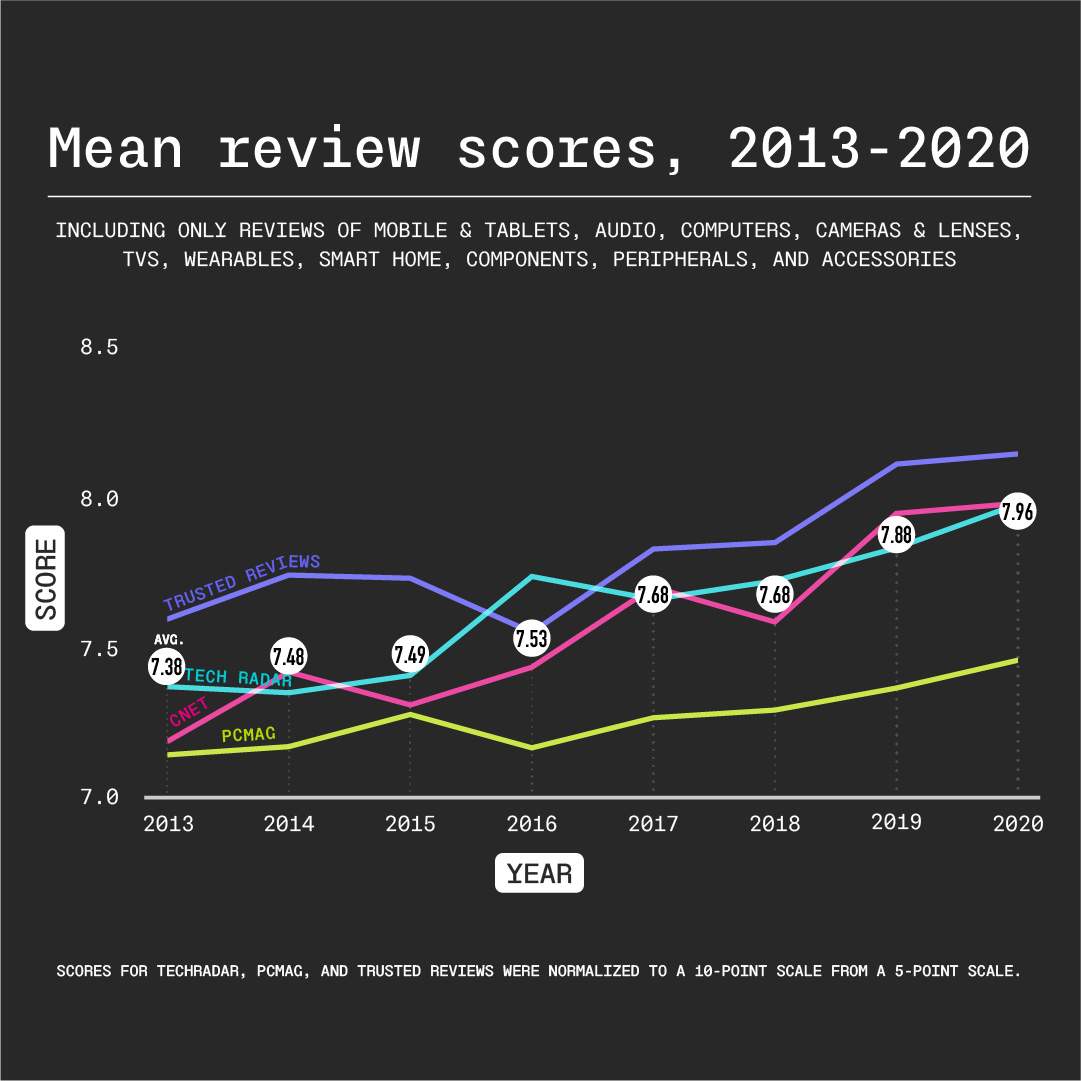

The already generous review system has only become even more generous over time, with the average review score increasing by more than half a point from 2013 to 2020, from 7.38 to 7.96. There are two things happening in this graph.

The first is a belief prevalent among tech reviewers that technology is getting better every year. This belief was exemplified in a 2020 video when Marques Brownlee, one of YouTube's mega tech influencers, interviewed Louis Rossman, a right-to-repair advocate and a paragon of an alternative model for engaging with technology; we'll revisit both figures later. In his interview, Brownlee suggested that the creeping disposability of our products might simply be the inevitable cost of progress. Brownlee draws from arguments by vendors against right-to-repair laws, citing device security, structural integrity, material desirability and manufacturing innovations as by definition necessitating a society-wide shift towards less repairable devices.

"With tech, tech keeps getting better and better and more and more well integrated and at the same time it's getting harder and harder to repair," he posits over B-roll of promotional footage for the M1 MacBook. "What does that future look like? It's kind of at a crossroads. Does the future of tech trend to get so good that it's trending to impossible to repair?"

The second phenomenon lurking in this graph is the increased synchronization between reviewers and product makers. While tech reviewers never held particularly scathing perspectives, their revenue also didn't directly depend on people purchasing those products until recently. But the cannibalism of ad dollars by Google and Facebook has forced media companies to come up with "innovative" business models, and for review sites, this has almost universally arrived in the form of affiliate links.

Today, every product review on every review site, whether it's scored at a 10 or a 5, includes a link to a seller with a code that, if the reader ultimately buys the product from that link, gives a portion of the sale to the linking site. The consequence is an alignment of incentives between publication and manufacturer, a vested interest in not merely acting as a reviewer, but as an advertiser.

At the same time, review sites depend on reliable, early access to products in order to publish reviews ready for the day of product launches. Given these publications' overall friendliness to manufacturers, it's hard to find ample evidence of companies withdrawing review products. However, it happened in the case of Gizmodo, when the Gawker-owned tech site published a leaked preview of the iPhone 4 in 2010. In response, Apple, along with filing a lawsuit against the site that demanded the writer's hard drive, closed off Gizmodo's access to review products, effectively shutting them out of early search results and losing a critical stream of review readership.

But what are the actual values enshrined in these scores? The relativistic parameters appear explicitly when looking at the 15 words most associated with high scores in reviews. While some words are generically positive across all critical domains ("superb", "fantastic", "amazing"), others bear particular significance within the context of consumer technology. Three concepts emerge:

-

Products are consistently compared with prior versions of themselves, and reviewers place a premium on change for change's sake, awarding points for technical or, more often the case, merely visual differences compared to previous models.

-

Rewards are given for a particular type of aesthetic dazzlement. While "beautiful" and "gorgeous" would seem to be generically positive words in the same way as "superb", they in fact reify specific critical values in the context of tech reviews, often elicited by products made of metal and glass.

-

Two words, "whopping" and "thousand", are associated with two distinct meanings, both conveying high prices and high technical specs (pixels, memory, etc.). While this confounds the signal of either meaning, here's an interpretation: products that are expensive and products that look good on spec sheets both get high marks; at the very least, a high price tag doesn't result in a marked penalty.

This paradigm, which rewards a combination of spec maximization, superficial sheen, and infinite redesign, and which does not even consider cost, did not come from nowhere. It was Designed by Apple in California, and with the crucial assistance of tech reviewers, it has since metastasized into nearly every other manufacturer.

The idea of evaluating consumer electronics based on the sort of aesthetic criteria as one would a sofa did not really occur until 1997, when Steve Jobs returned to Apple and met industrial design VP Jony Ive. In tandem, they began releasing candy-colored iMacs and iBooks as explicit rejoinders to the beige conventions of PC manufacturers.

One of the first machines produced under the Jobs/Ive regime was the Power Macintosh G3, whose curved edges and unconventional blue was a prototype for everything that has come since. In 1999, Apple released a promotional video that in retrospect can be read as a Magna Carta of the company’s entire design philosophy from the late 90s to today.

The video is worth watching in its entirety, from the Henry Kissinger “Power is the ultimate aphrodisiac” epigraph to the Marketing VP’s assertion that “If sex is power and the computer gives you power, there’s lots of sex in this machine” juxtaposed against a clip of Lara Croft, to a mustachioed Ive’s remark that “These have to be objects that are totally seductive...A computer absolutely can be sexy.”

Ive’s principal contribution during his tenure at Apple was to bake a Cupertino, California erotic sensibility directly into the company's products, communicated via computers' curves and materials and abetted by their spec sheets, particularly in a way that would appeal to viewers of advertisements. “To try and design an object that elicits a reaction of, ‘I, I really want that’ is enormously fun,” Ive says while mimicking a slack jawed consumer so overcome with desire that they’ve stopped forming full sentences.

In other words, it is in no way off the psychoanalytic deep end to argue that what Ive refined was the company's ability to stoke visually-oriented sexual desire. A more succinct way of saying this is that Ive introduced a framework of pornographic design, engineered for baser interests at the expense of others.

This pornographifcation of product design in consumer technology was not merely one of many influences on tech reviewers — it became the very paradigm under our current analysis. As Joshua Topolsky wrote of his time as editor of Engadget, “Stretching perhaps from the introduction of the first iPod in 2001, through the release of the groundbreaking iPhone 4 (and subsequent refinement with the iPhone 5), Apple was regularly lauded as best-in-class when it came to hardware and software design and the synchronicity of those elements.” The products that emerged from the Jobs/Ive Apple were the focal points the tech review apparatus used for its entire calibration, against which more or less all other products were judged.

For all of Jobs's sins as a CEO (completely closed systems, Foxconn factories, one could go on for days), his presence still mitigated against the worst of these tendencies, and his one virtue was a genuine focus on the experience of the end user. Despite Ive's sexualization, the usefulness of products like the iPod and iPhone are not difficult to argue for.

After Jobs died, however, Ive was given even more reign over product design when he was elevated to Chief Design Officer, a role that meant he oversaw the design of all hardware and software interfaces, including iOS, macOS, and tvOS. Before he ultimately left the company in 2019, the result of Ive's rising influence was a series of design blunders — the iPhone notch, the Magic Mouse that can't be used while charged, the AirPods Max that can't take advantage of Apple Music's own lossless audio, the list really does go on — as well as an even further pornographication of products. The materials the company used began to take precedence over the computing power they contained, with each generation of the iPhone boasting more and more durable glass, culminating in the “Ceramic Shield” on last year’s iPhone 12. Even Apple’s recent pivot into financial services has been largely justified on aesthetic grounds: the launch of the Apple Card was delivered with the tagline “Goodbye plastic, hello titanium,” with accompanying text bragging that the titanium its card is made from is “a sustainable metal known for its beauty.”4

The Apple Watch, too, has from the start been touted as much an as object as a personal optimization device. In a 10-minute promo video, Ive described the watch as “an unparalleled level of technical innovation, combined with a design that connects with the wearer at an intimate level to both embrace individuality and inspire desire.”

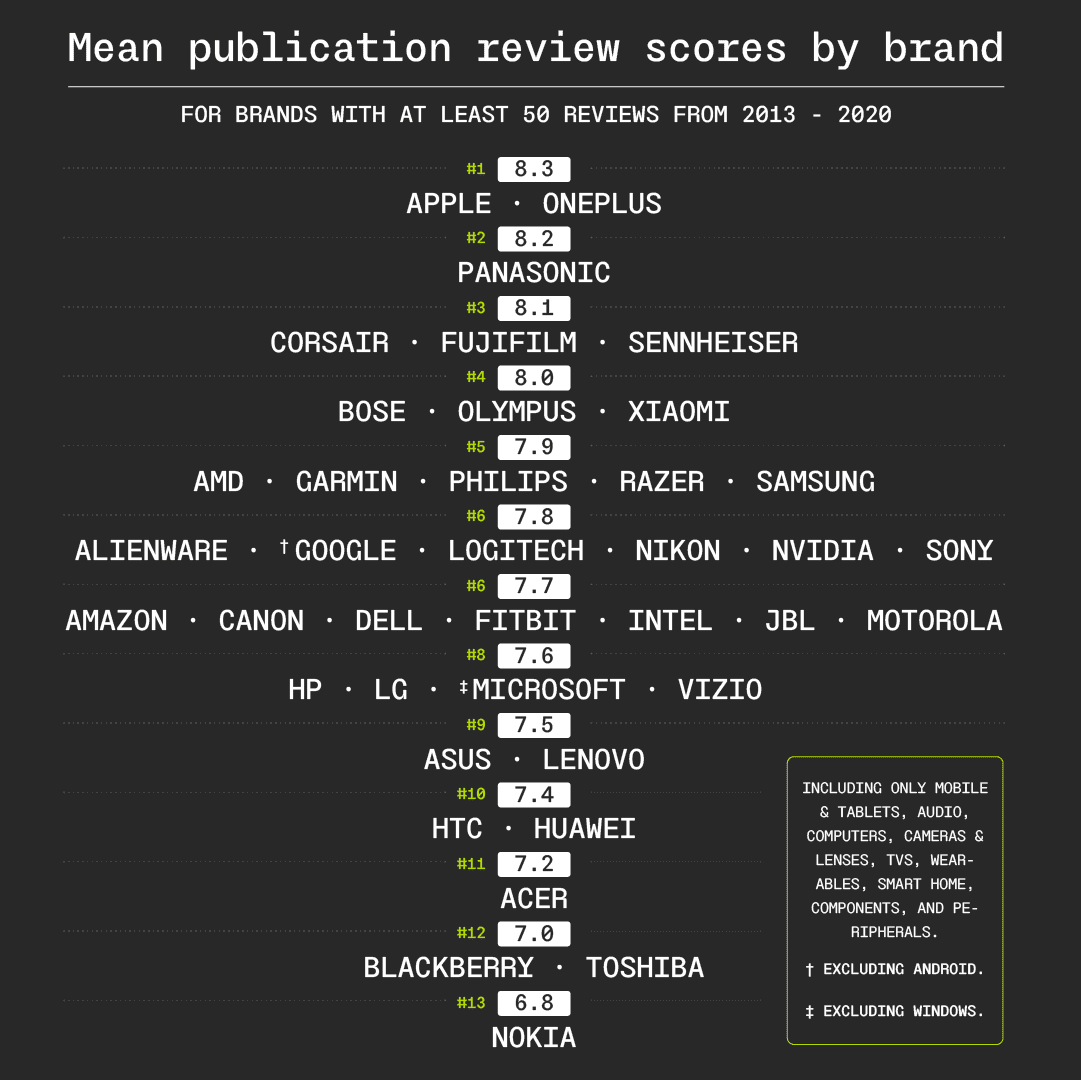

The diminishment of usefulness of Apple products throughout the 2010s inspired no revision of tech reviewers' assessments. Instead, the company's scores hovered in the mid 8's throughout the decade. Ive's pornographic design framework continues to calibrate the system — and by extension, the signals sent out to both consumers and competing manufacturers.

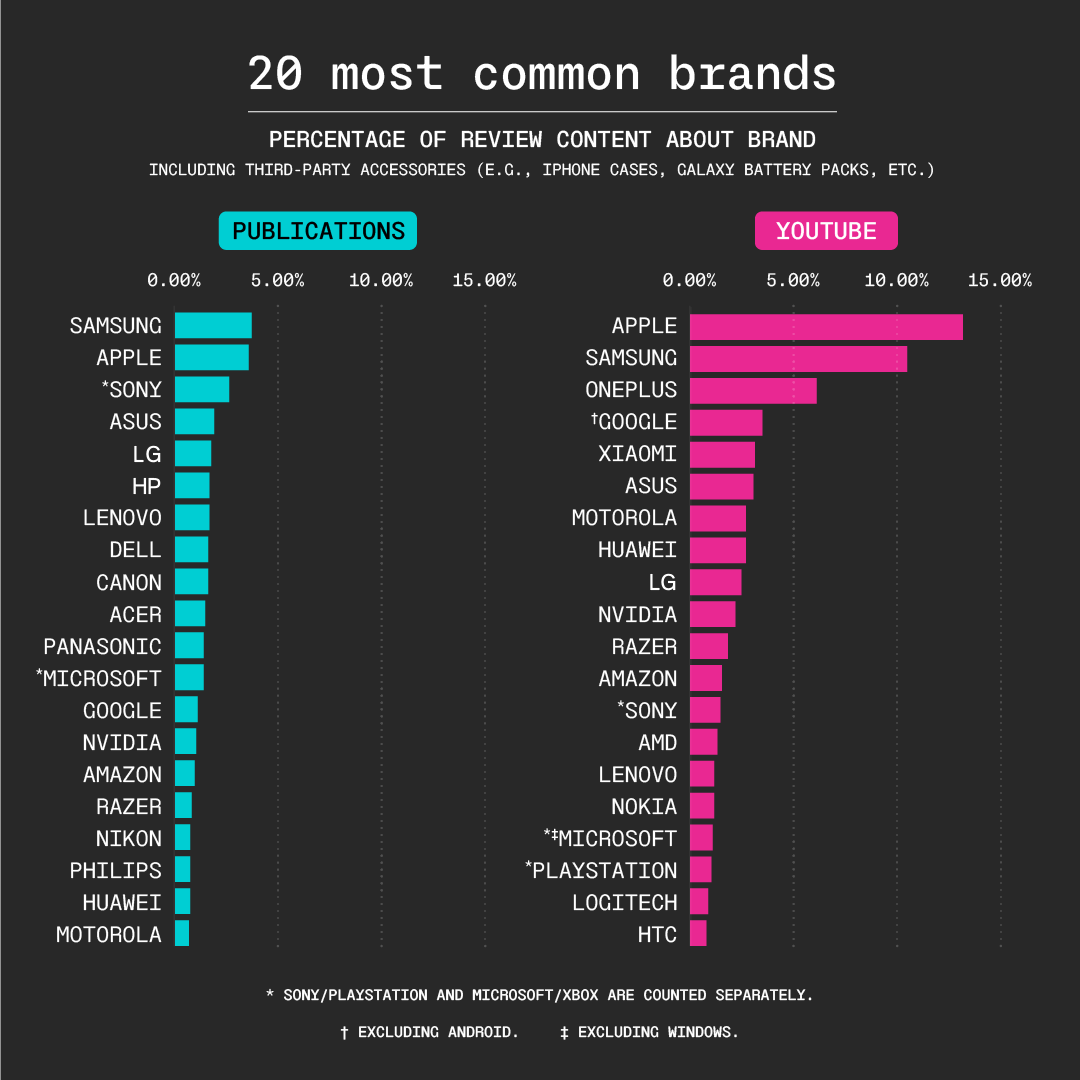

In response, the values of Apple's design paradigm have continued their transmission to other manufacturers, who have emulated its obsession with curves, shimmering surfaces, and even the blunders themselves, like the now nearly-universal notch. But only one company, the Chinese phone manufacturer OnePlus, has done so in a way that has rewarded it with top ranking among tech reviewers.5

Apple and OnePlus are the highest reviewed brands among tech reviewers, and OnePlus's place is a direct result of its attempt to replicate Apple's sexualized designs. "When we started out, there were many Android makers who wouldn't pay attention to the product," said Carl Pei, OnePlus's co-founder. "They were made of plastic and overall not good phones. We thought that there must be Android users who wanted a neat product, just like Apple fans do."

In 2020, Pei founded a new company, Nothing, whose first product is a pair of transparent AirPod-shaped noise-cancelling earbuds. As CNBC wrote, "Pei hopes his new company...will shape the consumer tech industry in the same way that Apple’s iMac G3 shook up the PC market in the late 90s and early 2000s. 'Today it’s like the PC industry in the 80s and 90s, where everybody made grey boxes,' he said."

For all the faults of tech publishers, they maintain two important qualities: the minimal resemblance of a critical process, and a conception of technology that extends beyond the smartphone. YouTube tech influencers dispense with both of these, and it is there that the distinction between review and advertisement fully collapses.6

Given YouTube's function as a video platform, the telegenic quality of contemporary tech that began with late 90s Apple is even more critical to products' reception by viewers. The seductiveness Ive introduced has always been made for TV, and that pornographic design has spawned the unboxing video, in which tech products are removed from their packaging, described, and embellished with professional high-grade lighting and camera work. Unlike traditional tech reviews, YouTube tech reviews and unboxing videos themselves become objects for consumption, and when people jokingly refer to them as "tech porn," they do so literally, whether they realize it or not.

This formal apotheosis is the ASMR unboxing video, which typically feature two gloved hands rotating, caressing, and tapping on product and packaging for upwards of ten minutes. These sensual movements provoke the tentative squeak of a phone being removed from its plastic cradle, followed by the moan of plastic being peeled of the screen.

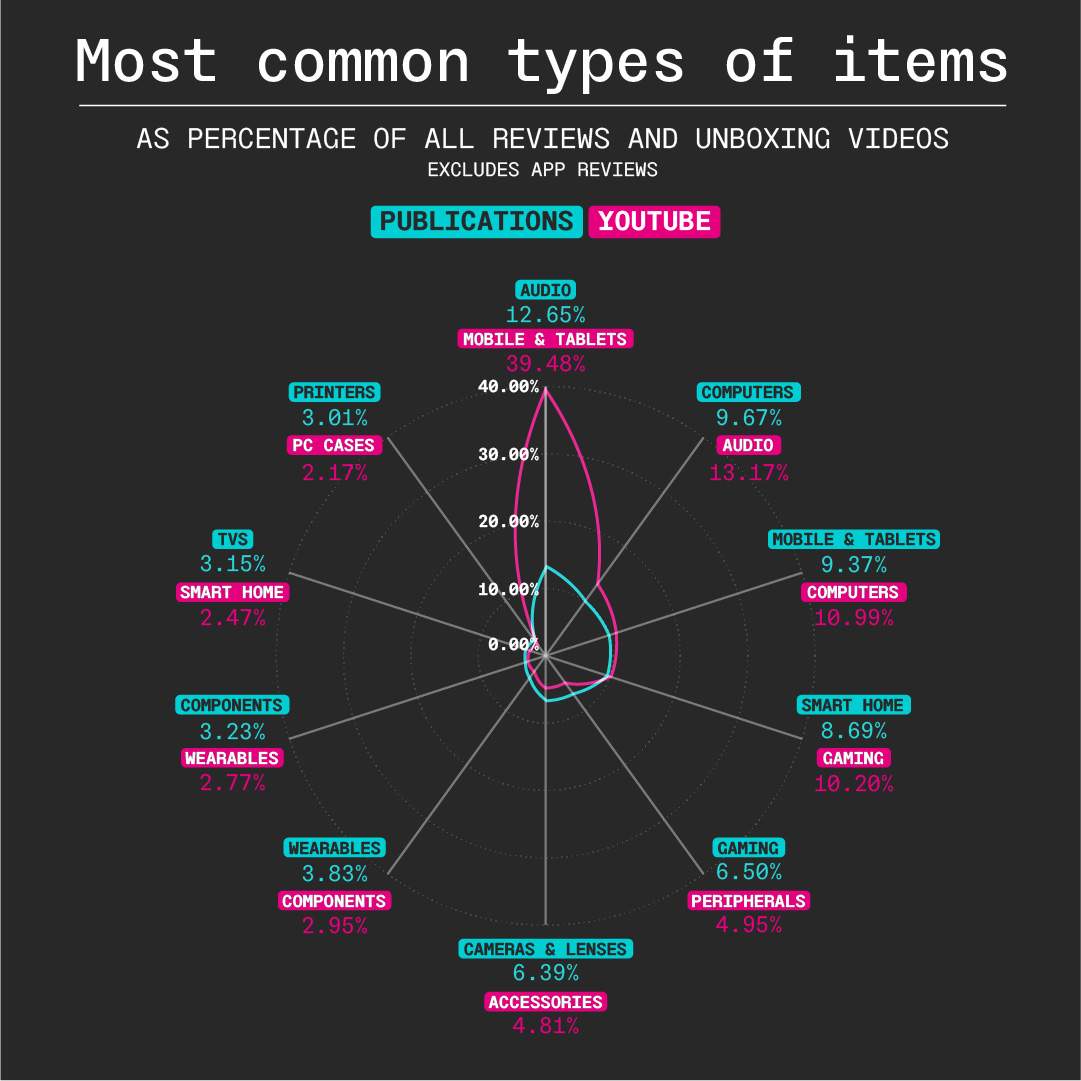

YouTubers have, relative to publishers, winnowed down what they review and unbox to a single product category. While smartphones and tablets7 comprise a little under 10 percent of traditional tech reviews, they make up nearly 40 percent of tech YouTubers' review and unboxing content.8 And publications are hemmed into a single review per product in a way that YouTubers aren't, where one phone review can be succeeded by endless follow-ups, pitting the "OnePlus 8 vs. iPhone 11," or a video three months later assessing if the OnePlus 8 is still "worth it," and on and on.

The telegenic qualities of mobile devices work with the platform in a way that other objects, like laptops, headphones, and GPUs, can't leverage. In turn, not only do mobile devices dominate the mindshare of YouTube tech channels, but manufacturers design products with even more fanatical attention to how the product will present in such videos, further cementing the device's target audience not as users, but as viewers. For example, companies have been explicit about the importance of the unpacking ritual. As Samsung published regarding their wearables packaging, "At times, the package of a product can induce a sensation that is as potent as, if not even stronger, than the sensation that comes from the product itself."

The centrality of Apple to tech publishers somehow pales to its role within the YouTube tech ecosystem. 13.2 percent of such videos are about Apple, compared to 3.6 percent of publisher reviews. OnePlus, despite having released only a handful of products in its entire history, is YouTube's third most covered brand at 6.1 percent, compared with less than one percent of publisher reviews, among whom it does not even rank in the top 50.

The natural result is a further consolidation of which manufacturers dictating what technology even is. If the iPhone, iPad and MacBook are the collective North Star of technology, then everything else — headphones, TVs, smart home gadgetry, anything — is evaluated not based on its ability to perform a specific task, its longevity, or anything else. Instead, they are evaluated on their proximity to that star, their resemblance to it, whether they can speak its language. All the other objects become no longer objects in their own right, but mere accessories for smartphones.

Before we dive into the consequences of all this, let's sum up where we've arrived so far:

-

Tech reviewers are broadly approving of the majority of products they evaluate.

-

Due to both financial interest (affiliate links and access to early release devices) and a general, personal lack of criticality, the tech review industry has become even more approving of these products over time.

-

Critical approval is reified in a sexualized critical paradigm that prizes endless novelty, spec maximization, and empty aesthetic sheen, regardless of whether or not these qualities come at the cost of usability. This paradigm was pioneered by Apple in the late 90s and has become only more lurid throughout the 2010s.

-

Through their scores, reviewers refract a paradigm of desire pioneered by Apple to both manufacturers and consumers, encouraging both to pursue the same design values. The company that has most tightly hewed to this code, OnePlus, has been rewarded with critical assessment on par with Apple itself.

-

This critical/design paradigm is even more concentrated on YouTube where the telegenic qualities of objects carry premium value and devices are able to be further fetishized through lighting and camera work. Accordingly, mobile devices have become the Alpha and Omega of technological consideration to YouTube creators and viewers, and the boundaries of who and what constitutes objects worthy of discussion has further narrowed.

That all of this produces hell-on-earth landscapes of e-waste is such trodden ground that it hardly needs repeating. These images and admonitions have proven time again to not have much of an ability to sway most people, including and especially tech reviewers. Instead, as fucked up as the need to even do this is, let's focus on consequences that are more immediate and less abstract to people in developed nations.

This waste itself is the result of a more fundamental consequence of the tech review paradigm: the creeping expansion of complexity, whose effects are borne in products' designs, manufacturing, and use.

By centering the smartphone specifically and the Ive framework generally, objects that previously were untouched by the caprices of tech trends now must desperately accommodate them. This is the premise of the Internet of Shit, a popular parody Twitter account that mocks the creeping technologization of once-simple objects, which the tech press has benignly referred to as the "Internet of Things". The current landscape of consumer goods offers boundless examples; the Bose Frames Tempo is one of them.

The glasses belong to a new product class that combines sunglasses and Bluetooth speakers that transmit soundwaves by vibrating the sides of wearers' skulls. Their purpose is ambiguous (one can presumably wear sunglasses and headphones at the same time), and joining the two functionalities in a single object diminishes the usefulness of either: Bone-conducting speakers will necessarily have less fidelity than sound received by your ears, while the complexity of the object makes it difficult for Bose to offer a range of styles and qualities of the glasses themselves. That means the model on offer, which looks like the stock accessory of a QAnon car-selfie avatar, is of a limited range Bose can feasibly design. Unlike an identical looking pair of Oakleys, the Bose Frames Tempo will, over the short span of a couple years, lose their battery capacity and be rendered useless.

The glasses received an 8/10 from the Verge, who in the relativistic fashion of tech reviewers, deemed them to have the "Best sound quality of all Frames."

Products like the Bose Frames Tempo also contribute to events like the ongoing chip shortage, which has inflated prices of consumer electronics and frustrated people looking for goods like the Playstation 5, which as of this writing is still out of stock in nearly every store worldwide. The complexification of products is accompanied by a complexification of their supply chains. The effect is cyclical: Placing chips in products makes all products with chips harder to acquire, and in making them more reliant on complex and fragile supply chains, delivery of needlessly complexified objects (like modern TVs, refrigerators and thermostats) to end users becomes ever more precarious. Ultimately, this means that objects which shouldn't need chips to function absorb them at the cost of those objects, like Playstations, that cannot be designed without them.

Complexification has also birthed a new type of painful user experience. Perhaps the most pervasive instance of this is the emergence of Bluetooth everything, a technology that more than 20 years after its introduction has not been able to remedy basic problems with reliability and connectivity. Bluetooth's user hostility was recently illustrated in a video by the YouTuber Ethan Klein, who challenged his mother to connect her phone to a Bluetooth speaker before he could solve a maze of mythological scale, a match Klein handily won.

This video shows a person unable to do something they want with an object. And while it provides an extreme example, no Bluetooth user exists who has not struggled with devices in a way that never occurred with wired 3.5mm adapters, a technology that Apple hunted down when it removed jacks from the iPhone 7 to force feed its users AirPods. Given the company's near hegemonic influence over how technology is designed, the removal was subsequently inherited by nearly every other manufacturer, and Apple's customers were forced into a new cumbersome choice: Adopt the company's proprietary AirPods (unserviceable and unable to retain 50 percent of their battery capacity after 18 months) for a smooth connection, use third-party Bluetooth devices (also largely unserviceable devices that lose their battery capacities) and incur the technology's agony, or maintain a wired connection with dongles that break every three months. No matter which path is taken, waste proliferates, previously robust devices are replaced with flimsy ones, and an object of compliance grows suddenly defiant.

In a moment of disconnect between reviewers and their readers, this move was widely derided by customers while remaining mostly unpenalized by the intelligentsia. CNET, PCMag, and TechRadar all gave the iPhone 7 an 8/10, while Trusted Reviews gave it a 7/10, and the ever generous folks at The Verge scored it 9/10. YouTubers dutifully unboxed and marveled at the phone.

Customers seethed and then, without much of a choice, relented.

In his book What Technology Wants, Kevin Kelly, the co-founder of Wired, coins the "technium" to denote "the greater, global, massively interconnected system of technology vibrating around us….The technium extends beyond shiny hardware to include culture, art, social institutions, and intellectual creations of all types. It includes intangibles like software, law, and philosophical concepts." Kelly sets out to describe the will of the technium, its teleology — what it wants. "In general, the long-term bias of technology is to increase the diversity of artifacts, methods, and techniques of creating choices," he writes. "Evolution aims to keep the game of possibilities going."

Whether in fact technology follows this arc in the long term is beyond the scope of this report, and really beyond the scope of anyone, as is Kelly's distinct Bay Area-ism of ascribing a will to technology itself.9 But in the short term of at least the past 10 years, which produced tech monopolies, massively consolidated power and wealth, refined dark patterns in user experience, and progressively stripped away any sense of agency from anyone with less than $10 million, it is difficult to look at the mainstream tools constructed in such a context and appraise them as tinder boxes of human potential.

As a counter example, it is worth looking to the not so distant past, when products were typically molded to fit the needs of users, rather than the other way round. The headphone jack of the original iPhone was slightly recessed, meaning an adapter was needed for audiophiles who wanted to use it with stereo headphones. That miscalculation was swiftly addressed in the space of a year, when Steve Jobs unveiled a flush headphone jack on the iPhone 3G to uproarious applause. It was a simple tweak, but an important one, for the obvious reason that it expanded the iPhone's communicativeness with other products, making it more useful.

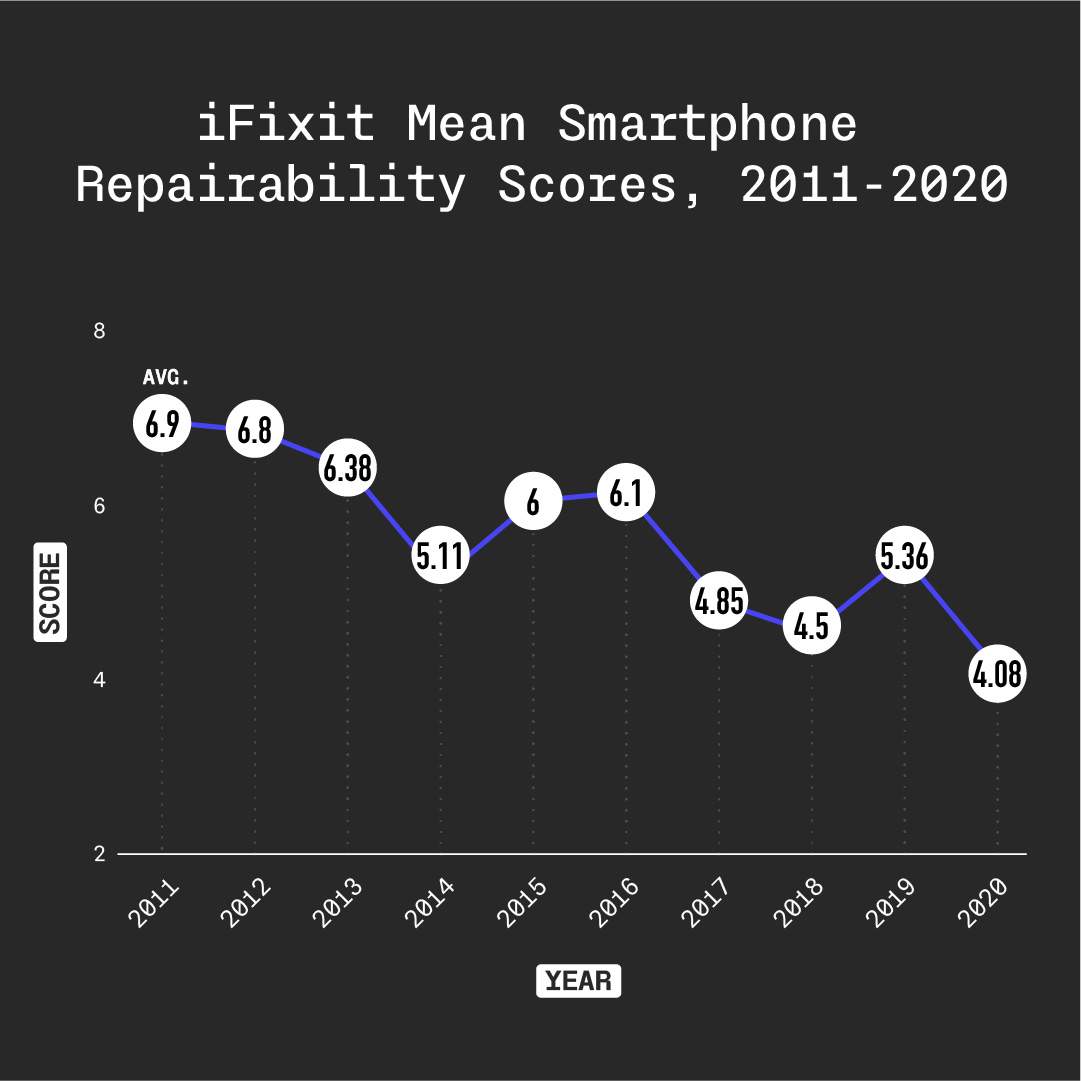

There is one final, important counterpoint to the narrative of technological ascension and possibility expansion. This is the mean repairability of smartphones as scored by iFixit, the repair company based in San Luis Obispo, California. iFixit is a small outfit, and so there's a relatively small number of devices for each year, ranging from half a dozen to 20. It's not a lot of data, but it doesn't matter — the diminishing repairability of consumer goods is now canonical among researchers. Products are less fixable both intentionally, via completely avoidable construction choices like glued batteries and proprietary screws, and because the tech review aesthetic demands a maximization of sleekness and thinness. All of this adds up to fetishized sheen, never mind the cost to the product’s longevity.

This is not a report about right-to-repair; for now, we can suspend any concern with the actual ability to repair products, shortened life cycles, toxic waste, and terraforming the planet so that it overflows with garbage.

What matters is that the potentiation of will is the only meaningful criterion against which tools can be evaluated. And just as Bluetooth thwarted Klein's mother and the vanishing ports stifled teachers, the inability to open, repair, experiment with, and find new uses for an object is a contraction, not expansion, of choice and possibility that constitutes a brick wall blocking the operator's will.

A truly user-focused review paradigm would map out the ways a user seeks to channel their will through an object and examine how that object potentiates or blocks that volition. This sounds simple and straightforward; reviewers would likely argue that they already do this. But if they did, the products they evaluate wouldn't be assessed as works of art on a relativistic score distribution, mostly good, many great. Instead, they'd be treated as tools that can either help or hinder the user, scored entirely according to where they fell on the continuum between useful and useless.

To address this, there are two broad non-legislative10 remedies.

The first is to hold reviewers accountable for their credulousness in an attempt to push them in a more genuinely critical direction. This is not as futile as it might seem. In July 2021, Linus Tech Tips, one of the largest YouTube tech channels at nearly 14 million subscribers, published a raving review of the Framework laptop, a completely modular computer that allows users to easily order and replace every single part of the machine, making it a more durable, flexible, user-focused design than most anything else on the market. Linus was so impressed by the computer that he pre-ordered one on the spot, and the traffic directed to Framework afterwards temporarily overwhelmed and crashed the company's website.

Linus's review of Framework not only directly demonstrates publishers' and influencers' ability to drive demand, but that that demand is in fact malleable. As the scholar Rene Girard theorized, desire is not inherent, but follows the desires of others ― I want what you want, because you want it. It is not an exaggeration to estimate that a dozen videos expressing desire for products built on a set of values contrary to those of the current regime would be sufficient to recalibrate an entire system of industrial design.

A second response is to embolden those critics who are already working in alternative paradigms. Louis Rossman, who runs a repair shop in New York, has built up a 1.6-million subscriber channel and has become one of Apple's most prominent critics, taking them to task for their increasingly user-hostile designs. His impromptu comparison of a Motorola phone and a Samsung, despite his self-deprecations, functions as an exemplar of anti-fetishistic tech criticism, interested solely in the day-to-day experience of use and whether the object conforms to the user's will.

As an example of how a publishing endeavor might look, Mark Hurst, the founder of design consultancy Creative Good, maintains Good Reports, a thoughtfully compiled Wirecutter-esque set of lists of the best tools that function as viable alternatives to those of extractive tech companies. Hurst's recommendations can at times verge on Luddism — his recommended phone is the Light Phone, a black-and-white app-less device whose most powerful messaging tool is SMS, a product that can't be sincerely recommended to any member of society in 2021. But despite its sometimes excessive contrarianism, Good Reports provides a working prototype for how an operation premised on a critical paradigm might look, and one can imagine it expanding given more resources.

When Apple announced the iPhone 7 at its 2016 keynote event, Phil Schiller, then the company's marketing chief, offered the company's now legendary justification for removing the device’s headphone jack to preemptively deflect the inevitable blowback against a decision so transparently hostile to the phone's users.

"Now some people have asked why we would remove the analog headphone jack from the iPhone," said Schiller, who happens to be frequently quoted in Epic Games's lawsuit against Apple as one his employer's chief lock-in strategists. "I mean it's been with us a really long time. I'm sure you know that the source of this mini phono jack is over 100 years old, used to quickly exchange on switch boards. Well the reason to move on — I'm gonna give you three of them, but it really comes down to one word: courage. The courage to move on and do something new that betters all of us. And our team has tremendous courage."

The self-heroizing spin was too much for even the tech publications to resist piling on in their blog posts (before they awarded the phone good to great marks), and it immediately became a symbol for the mixture of PR, market cannibalism, novelty obsession, and user manipulation that has come to define contemporary consumer technology.

But building a product designed to be as useful as possible to the consumer even at the cost of superficial seduction, or refusing to endorse one that abuses its customer relationships at the risk of alienating the manufacturer — that does take courage. Hopefully its absence, amid a pervasive disenchantment with plutocracy, has finally hit bottom.

If you liked this report, you can sign up for Components' very periodic newsletter here. You can also contact us at mail@components.one.

This report was produced in collaboration with

You can follow their founder on Twitter and sign up for their newsletter here.