Summary

This report is the result of an analysis of Product Hunt from 2014 to 2021, including 76,822 products and 397,067 user profiles. Among its findings is that users who promote productivity apps and users who promote games are the least likely to be the same people, among any pair of categories.

We argue that this opposition is a reflection of two nearly irreconcilable value systems. The first system, belonging to the person we have dubbed the nihilist, views productivity app usage as a means to reduce wasted time, but ironically turns this usage into an end in itself. This results in the appearance of productivity, but the actual production of relatively little. The second system, belonging to the person we’ve dubbed the gamer, situates the fun of gaming as an end in itself, which disincentivizes them from activities that eat into time spent having fun, such as faux productive behavior. The gamer equates waste itself to value, and can clearly separate utilitarian from non-utilitarian activity. The nihilist, on the other hand, is unable to explicitly value waste, and thus wastes time in a meaningless way.

These opposing systems animate the types of organizations that cater to each persona: the perennially unprofitable venture-backed startup, for which faux productivity is connected to the generally immaterial nature of its high valuations, versus the game studio that lives and dies by the profitability of its products. The irreconcilability of the nihilist's and gamer's understandings of value is made manifest when the former's framework commandeers the latter's, resulting in compromised games (as in the case of Microsoft), or the appropriation of games into work and financial speculation (e.g., play-to-earn crypto games and the tokenized metaverse more generally).

The earliest work on this project began in 2020, and the bulk of it took place in late 2021 and early 2022, during a continued period of euphoric valuations of both tech stocks and cryptocurrencies. As we finalized this project, both nosedived from their pandemic peaks after inflation concerns forced central banks around the world to raise interest rates. We hope this report provides worthwhile material to consider for creating organizations that require more than low interest rates to thrive, and to reflect on the meaning of value itself.

Introduction

Product Hunt, the internet's largest social network and clearinghouse for apps, launched in 2013 when founder Ryan Hoover decided to build a central location to replace the word-of-mouth process his peers used to promote tech products they liked or had built. The result was something of a twist on Reddit, but for software, relying on three types of users to function. There are the Makers, who build and release products on the site; the Hunters, who sponsor a product by promoting it to their followers (each product can only have one Hunter); and the audience, which upvotes and comments on individual products.

Within three years, Product Hunt had become so vital to product launches — Zapier, Notion and Slack are just three of the companies once publicized there that went on to multi-billion dollar valuations — that it was acquired by AngelList for $20 million. Today, Product Hunt remains a key scouting location for venture capital firms looking for new investments; the site is "a must-read website in the VC world,” according to one firm partner, and a place where "venture capitalists flock to…as a sourcing mechanism", as another put it. The interest of VCs in Product Hunt is well justified, as one analysis found that "an investment strategy based on Product Hunt votes would have outperformed the majority of funds out there."

As Product Hunt flourished under AngelList, Hoover embarked on the obvious career pivot by becoming a VC. In 2017, he founded the Weekend Fund. Four years later, Product Hunt itself spun off Hyper, an accelerator fund. Earlier this year, both Product Hunt and Hyper were packaged together into a single holding company called Prologue, which was given $23 million in funding from goliath venture firms Andreessen Horowitz and Sequoia Capital.

Product Hunt's outsized role in the startup economy makes it a rich, semi-structured proxy for analyzing the broader paradigm of Silicon Valley — as a mirror of where VC attention is directed, of the tastes and interests of aspirational product designers, and as a imprint of the undergirding mores internalized by tech's inhabitants.

Analysis

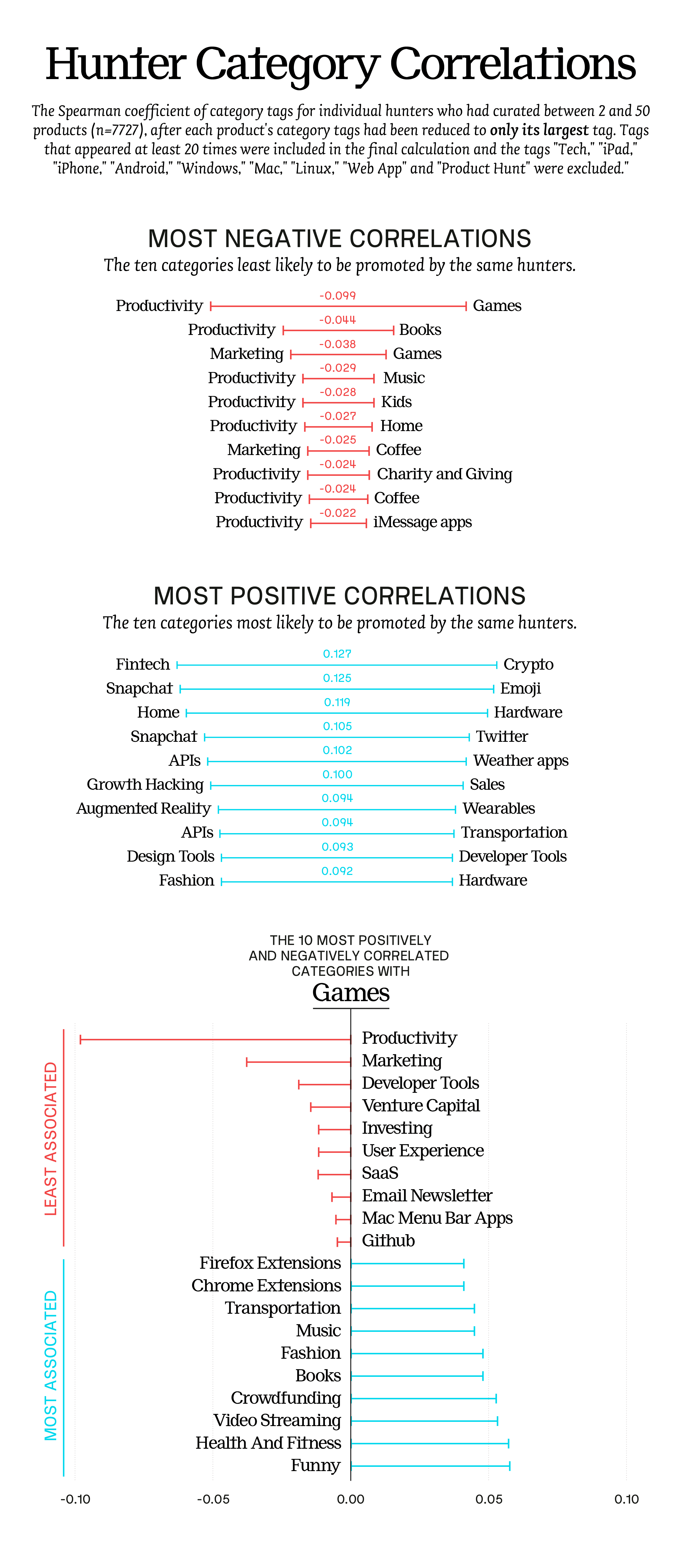

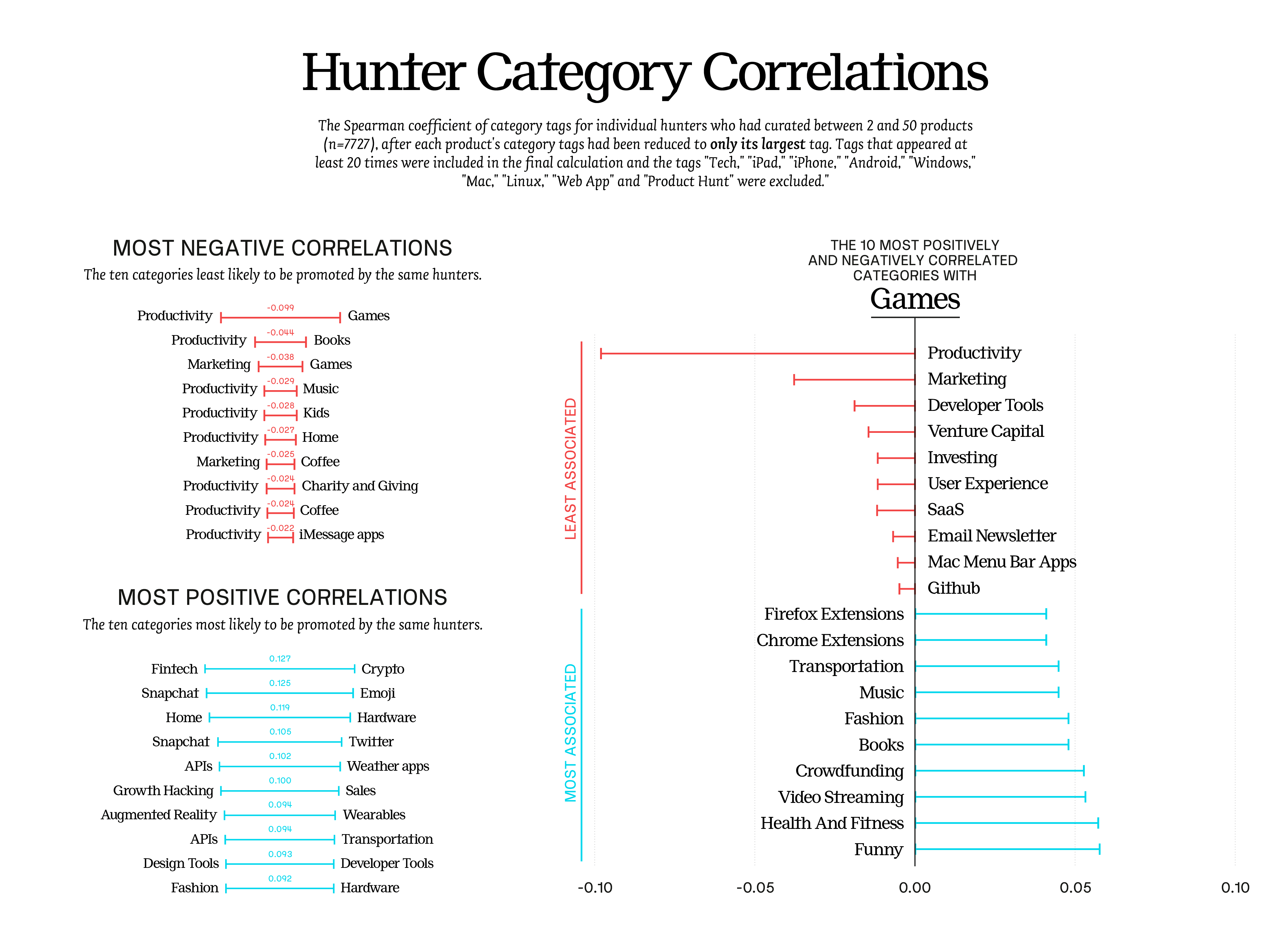

Summary: Reducing sets of product category tags to only the largest category tag for each product reveals that Hunters who promote games are the least likely to promote products related to productivity, and vice versa.

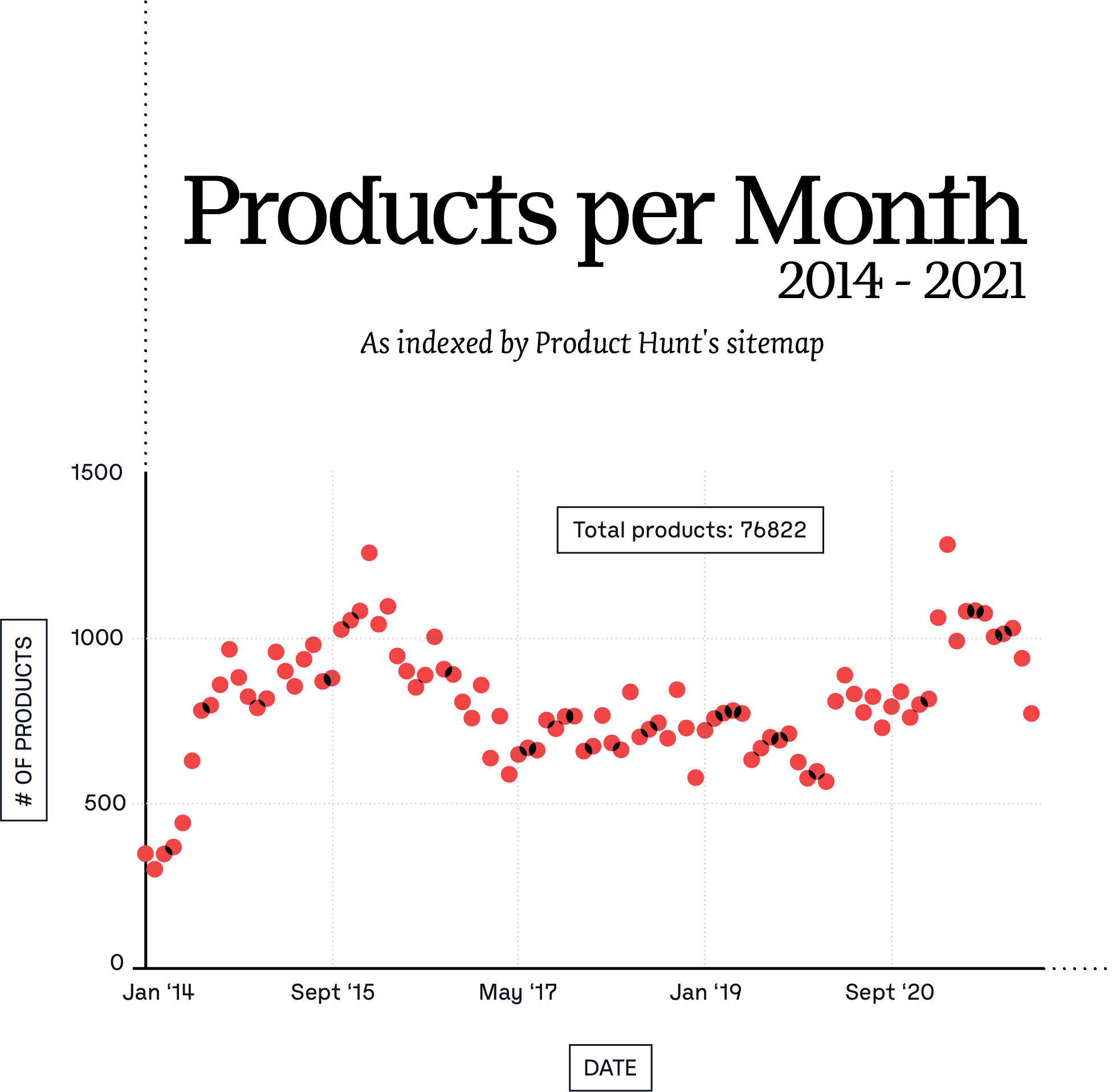

Let's start by situating ourselves on the map. This is how many products appear in the data on a monthly basis, beginning in 2014 (Product Hunt’s first full year) and stopping at the end of 2021.

Whether this represents the actual number of products released on Product Hunt throughout this period is difficult to determine. The products and user data that appears in this analysis is based solely on the Product Hunt sitemap, and anecdotal experience indicates that not every product gets indexed there. But given the general smoothness of the curve, and the overall number of the products here (more than 70,000), it's as large a sample as one is liable to get.

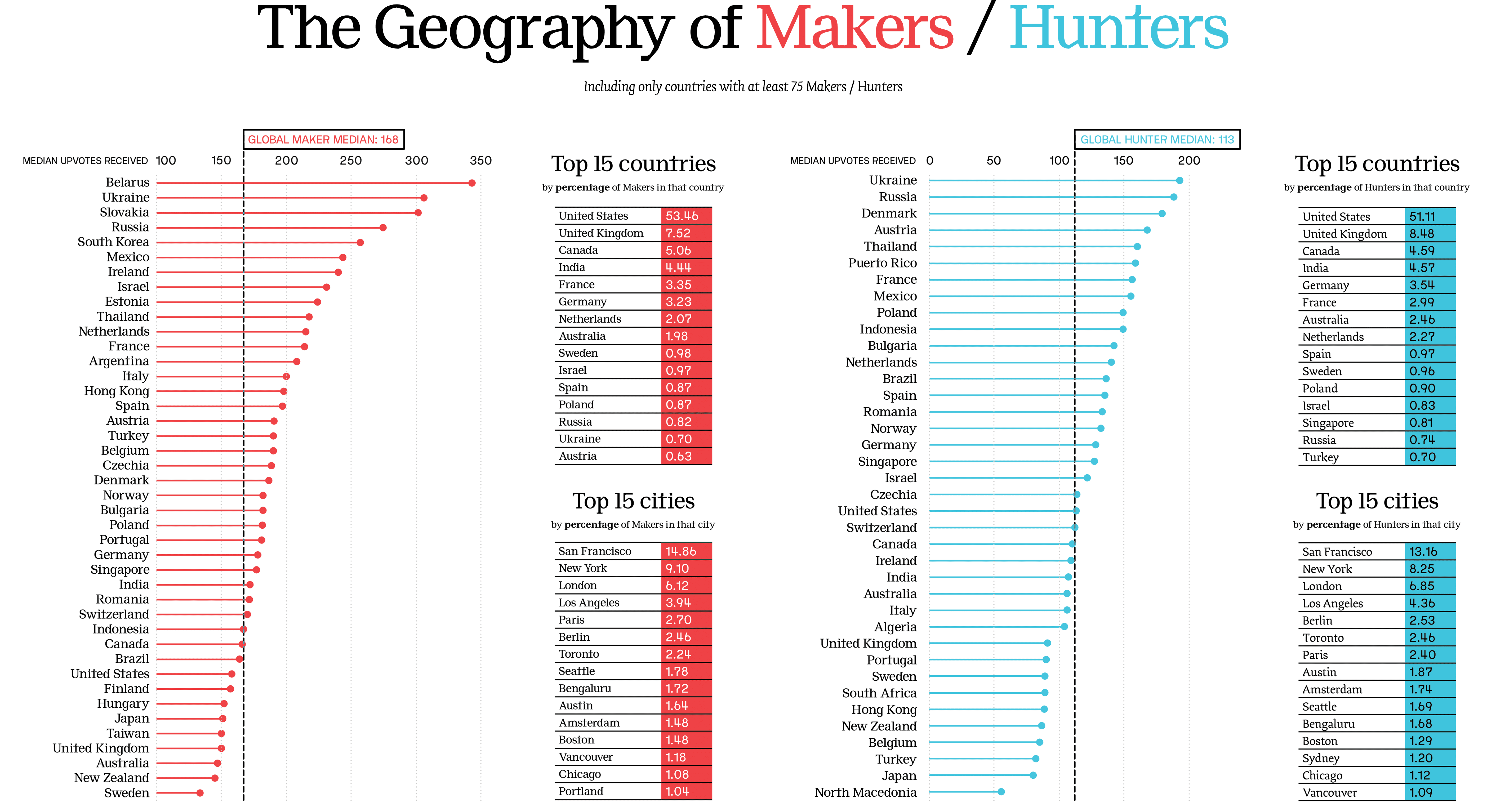

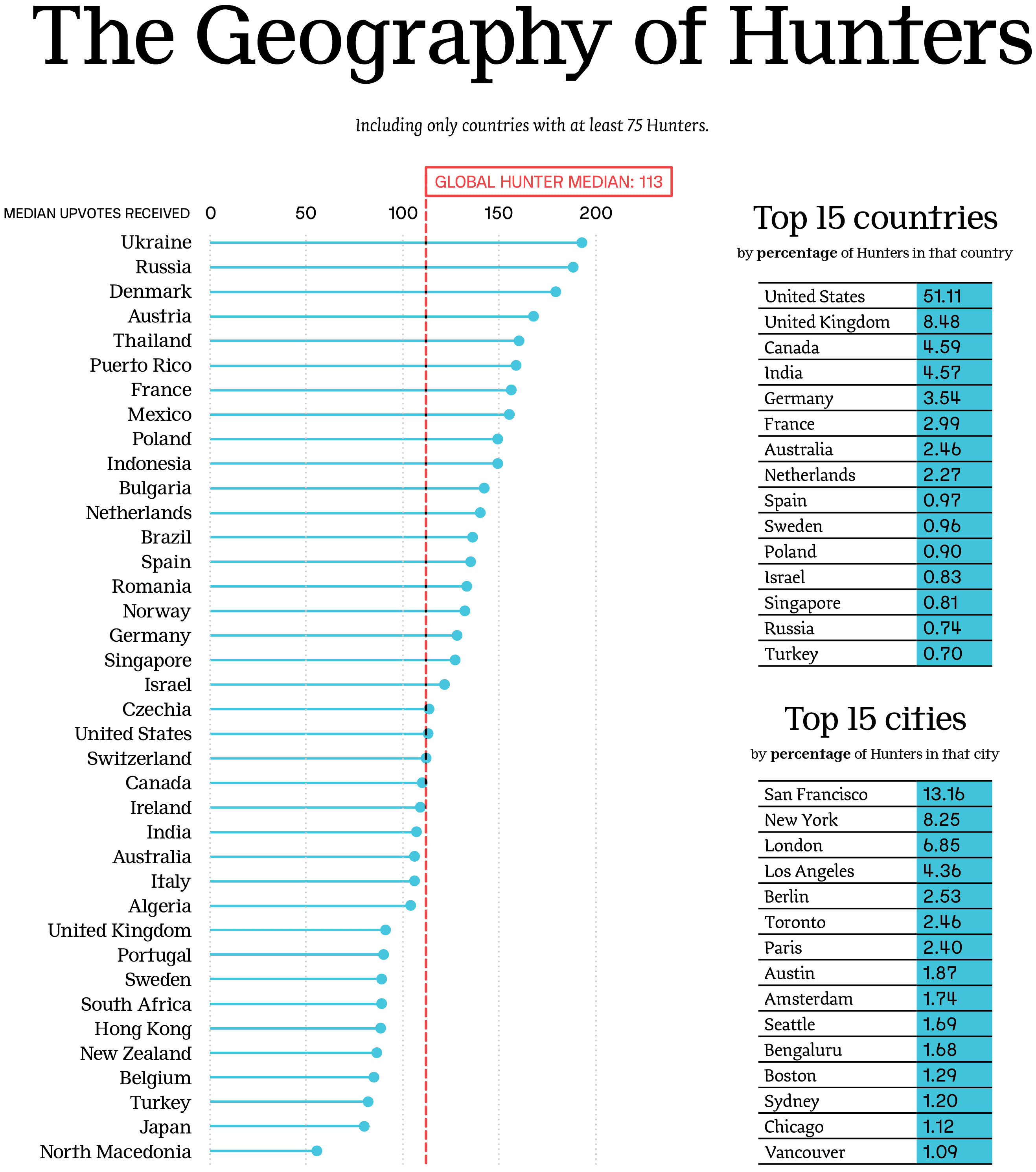

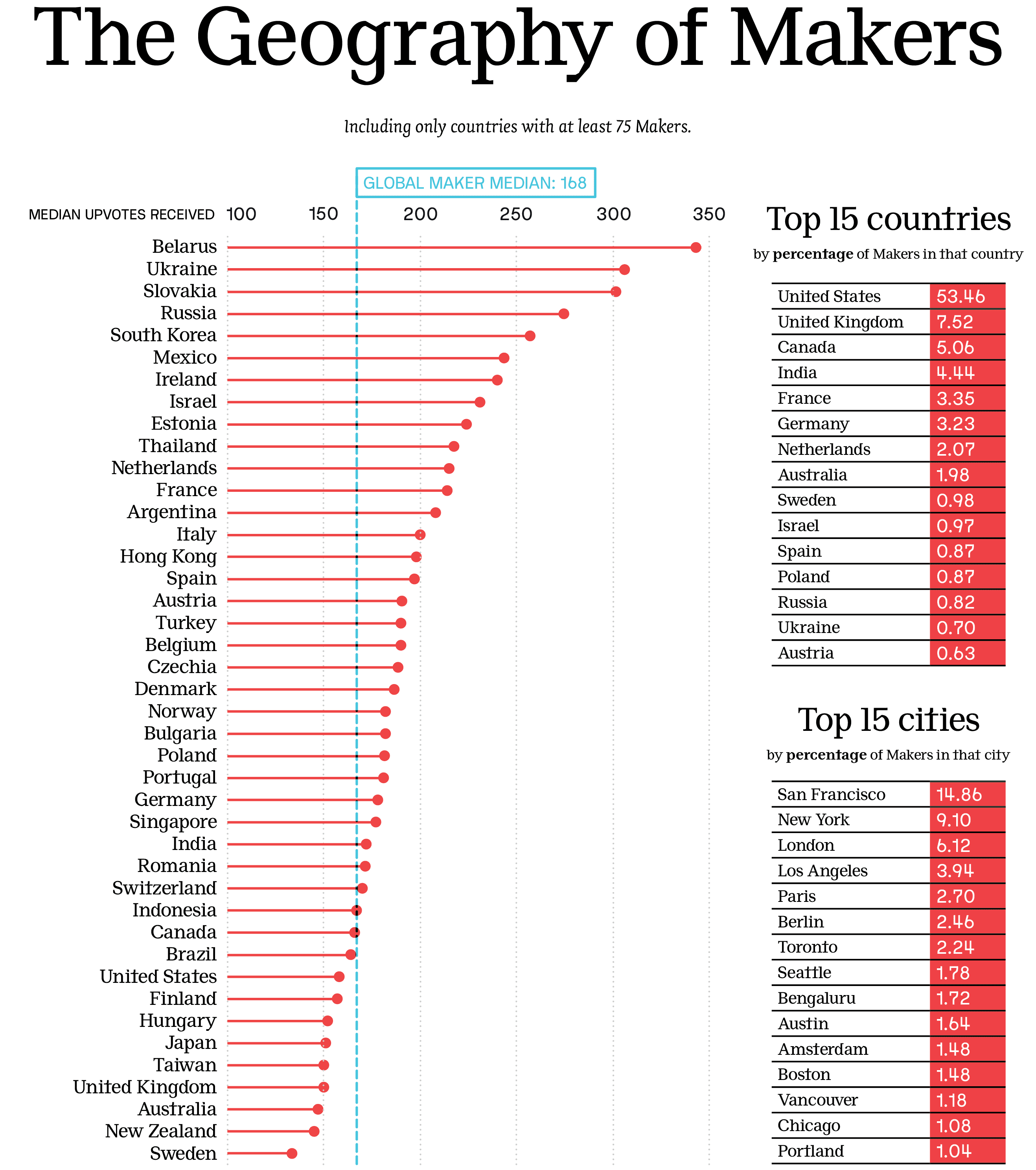

The geographic data below is based on self-reported information on people's Twitter accounts, which many link to from their Product Hunt user profiles. In all, 158,329 profiles linked to Twitter accounts have usable country information (e.g., "US" and "United States" can be normalized using the Google Maps API, but "🌍" and "NY/SF/London" can't be), and 124,073 usable city information.

Some results may surprise (the dominance of Ukraine and Russia among upvoted Makers and Hunters, for instance) and others may not (the disproportionate occurrence of Americans, and specifically San Franciscans). The higher global median for Makers versus Hunters is due to the fact votes are counted for each product's Maker for each unique country. As we discovered, the more Makers a product has, the more upvotes it receives.

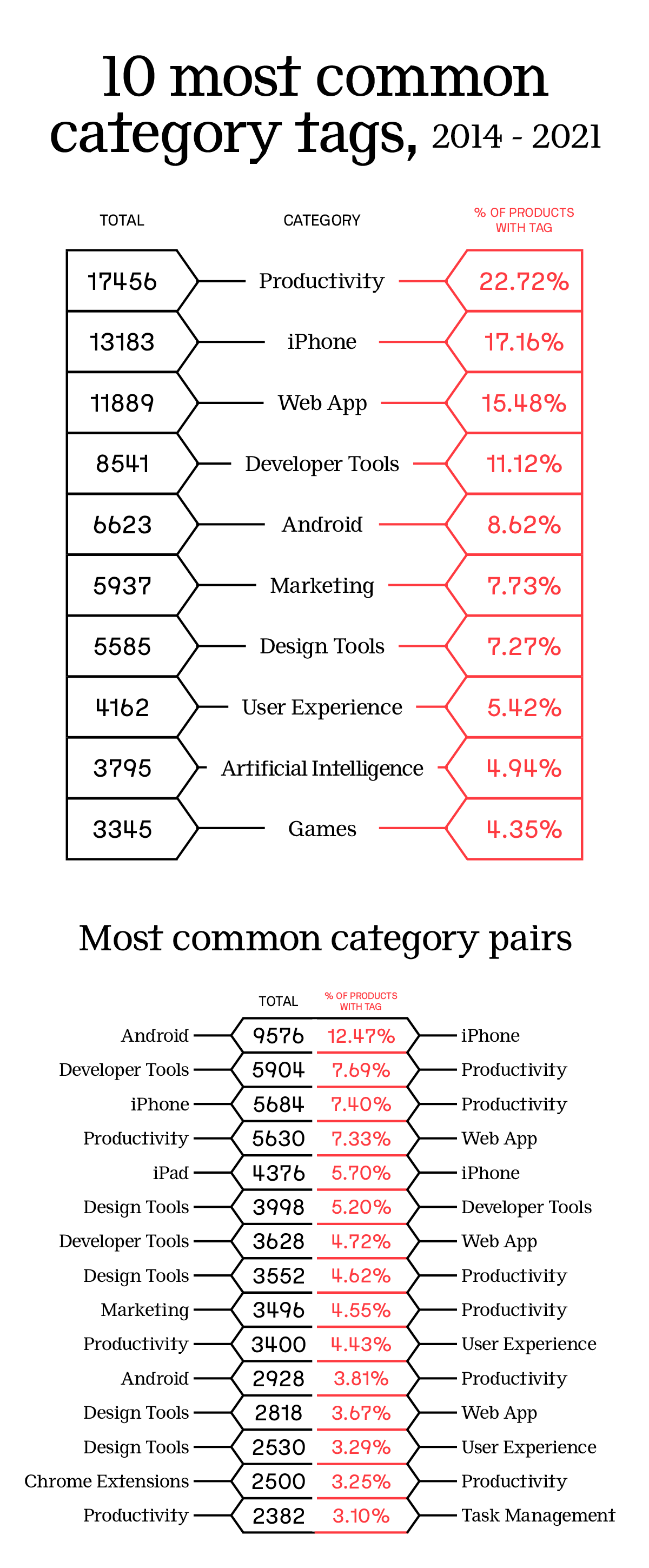

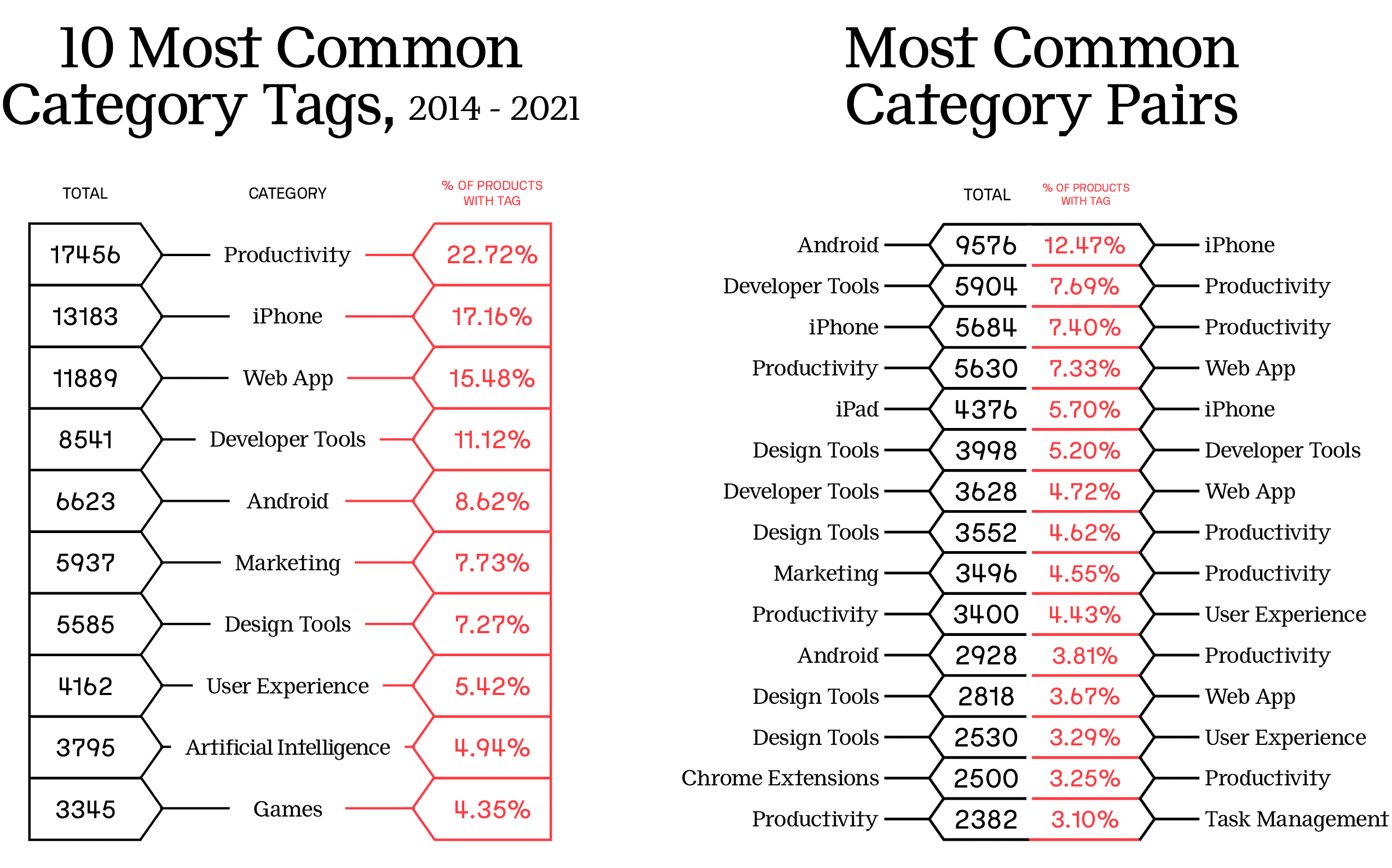

Every product profile on Product Hunt contains a set of category tags. Users can follow these topics and receive notifications when new products with those tags are released. (One tag, "Tech," was removed from our analysis because of its ubiquity early in Product Hunt's history.)

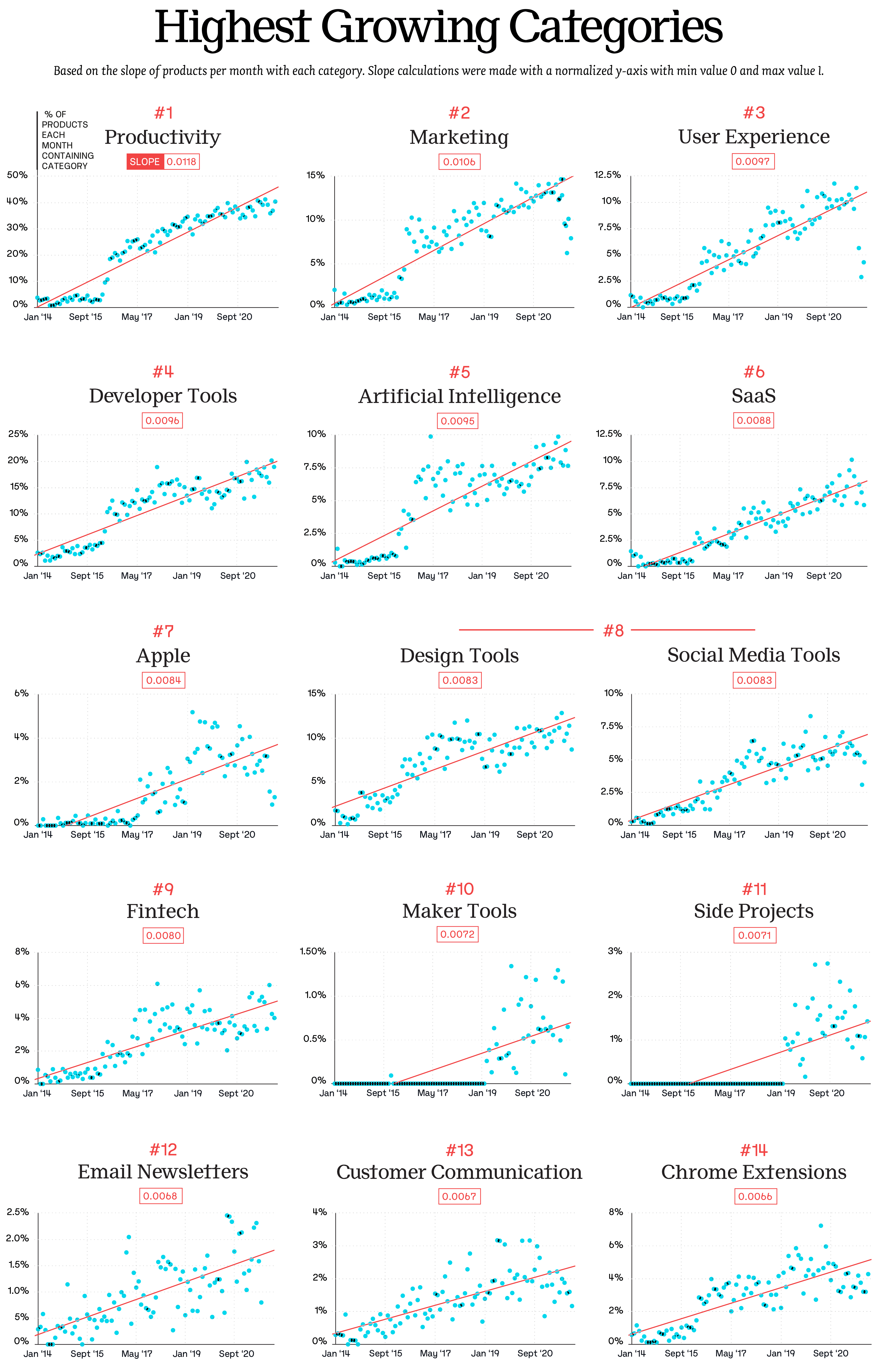

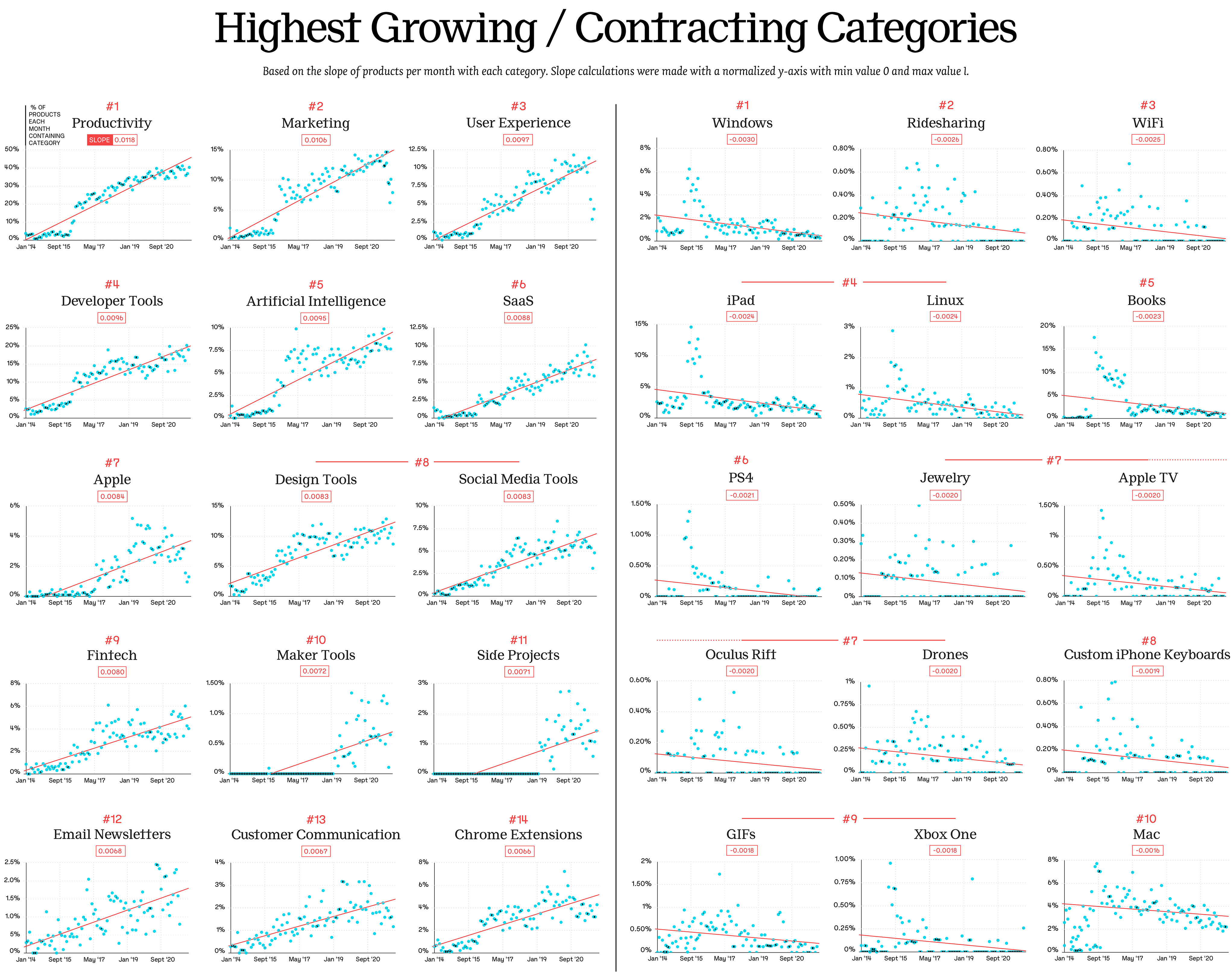

Since our thesis rests on the interplay of these tags, let's start by looking at them broadly, at both the most common tags in their own right as well as the most common pairs of tags. (The y-axes of these proportions were min-max normalized for each category when calculating the slopes.)

Looking at how these categories have grown since the beginning of our dataset gives a sharper view of how dominant the most popular tags became by the end of 2021. Aside from the platform-oriented categories, the overall most common categories also have grown the most as a proportion of total products, observed by calculating the slope of the proportions of products with a given category over the whole time period. "Productivity," "Marketing," "Developer Tools," "Artificial Intelligence," and "SaaS" are the biggest gainers. In 2021, the "Productivity" tag was included in 39 percent of all product listings.

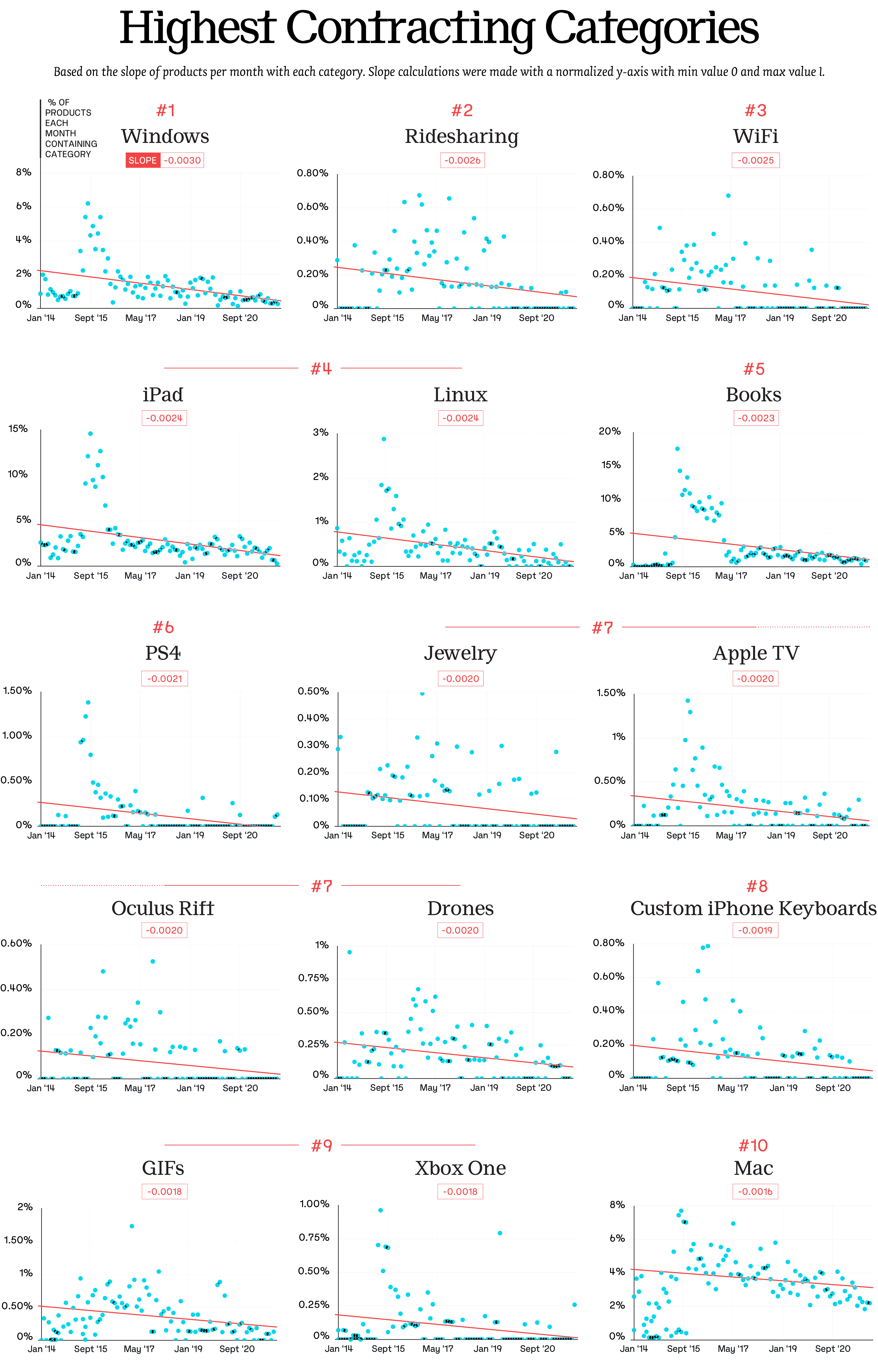

Calculating shrinkage is more difficult and less exact, since some categories temporarily spike (the fact that these spikes all seem to appear in the same place raises questions about Product Hunt itself and its standards for categorization, as does the sudden, precipitous drop in some of the categories in our growth chart). Obviously, most of these curves aren't linear. As a predictive exercise, using a linear model here would be forbidden, but as a merely descriptive exercise, it tells us what we need to know.

Importantly, the results all map to basic reality. The diminishment of operating systems — "Windows," "Mac," and "Linux" — corresponds to software-as-a-service (SaaS) web apps solidifying their dominance as a delivery system for software over the studied period. The near disappearance of "Ridesharing" coincides with the dried up interest in building third-party apps for (or, more certainly, alternatives to) Uber and Lyft. "Custom iPhone Keyboards" are a category of product whose existence we had forgotten about until seeing their downfall here. And the occurrence of three game-related tags — "PS4," "Xbox One," and "Oculus Rift" — are meaningful not only for appearing together, but for signaling a broader disinterest in gaming on the platform over time. The "Games" category, while the 10th most popular tag overall, was 20th in 2021. And as we'll see shortly, games underperform nearly every other category on the site.

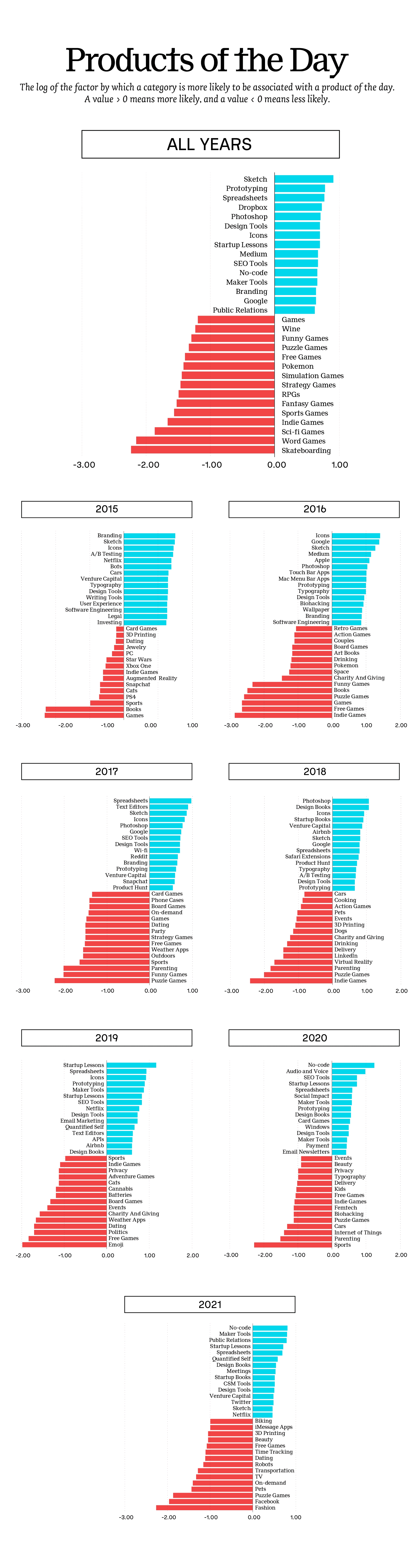

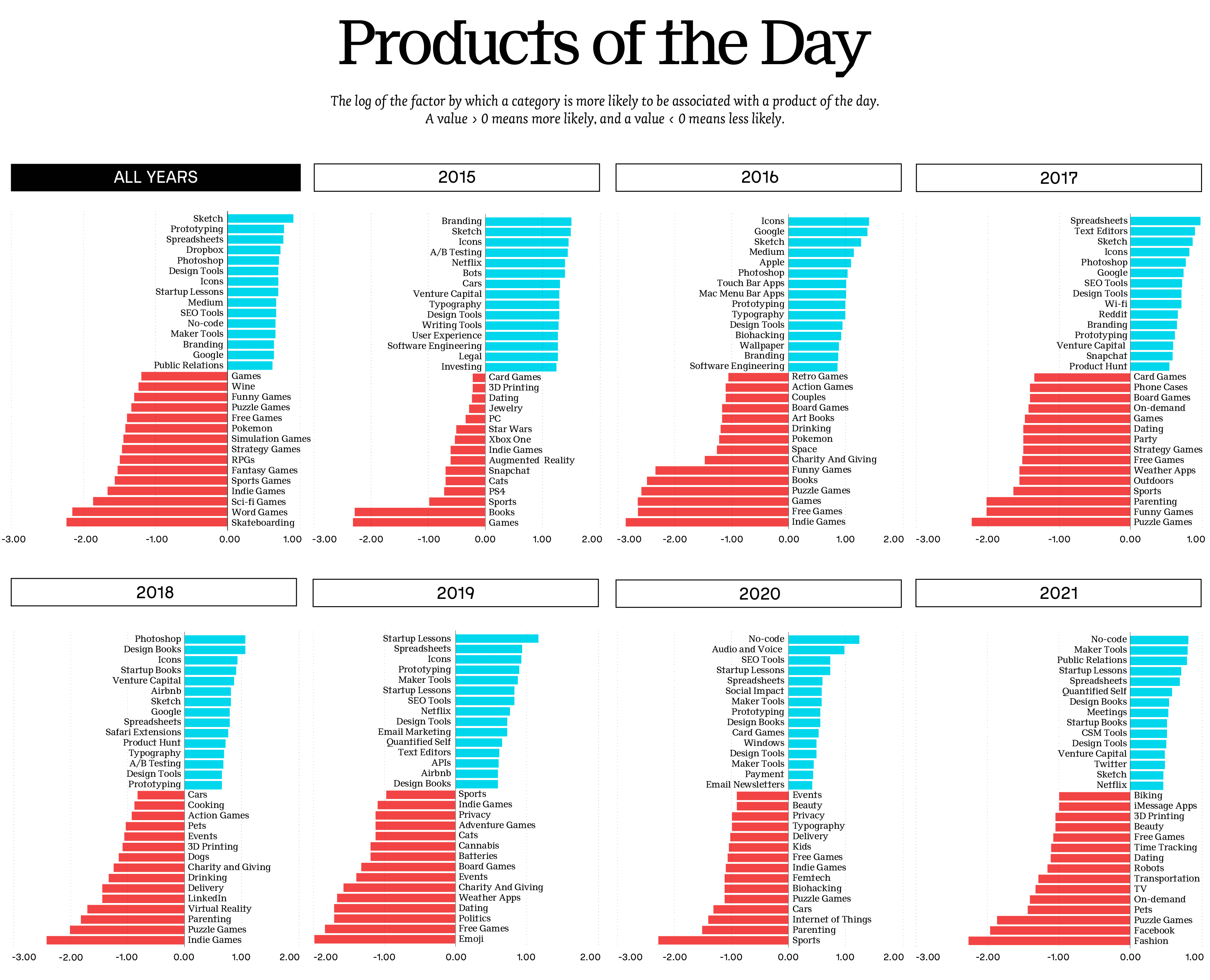

To examine what types of products people on the platform generally like, it's more useful to look at which categories are most and least likely to be voted into the Product of the Day rankings (reaching the rankings was all that mattered, the order of the rank was ignored) rather than looking at upvotes, as those numbers fluctuate.

The patterns among the top ranked products are relatively straightforward, and at the bottom, they are resounding. Games and their subcategories are the least likely to receive top recognition on the platform. Perhaps this is because Hunters are more likely to promote amazing spreadsheet-type apps and less likely to promote good games. Or maybe it has to do with the nature of the platform itself: it's easier to quickly grasp the intention and capabilities of a new prototyping tool than it is to fully evaluate The Witcher 3 (a game Hunted on the site).

What follows in the rest of this report is an argument that neither of these arguments fully explains the broad rejection of games on Product Hunt. To that effect, let's examine one last graph.

This graph shows which categories correlate among Hunters themselves. To examine this, every product's set of categories was reduced to only its largest category. For example, if a product's tags are “Games,” “Raspberry Pi,” and “Batteries,” and if “Games” appears more often in the entire dataset than the other two, that product's category tags will be reduced only to “Games.” Only Hunters with at least two and fewer than 50 hunted products were included, and only tags that occurred at least 20 times among them all were included. We then looked at the Spearman coefficient for every pair of categories.

Negative values mean a Hunter who promotes X category is less likely to promote Y; positive values mean the opposite. The categories in the visualization, in addition to gaming, include every category for which gaming was the most negatively correlated category — i.e., those most likely to be hunted by people different than those hunting gaming products. There are some caveats to state outright, mainly that not every relationship in this graph is necessarily meaningful, or at least not obviously so. Many of these values fall into top-10 territory despite being quite small comparatively. Whether people who like games really are disproportionately interested in “Firefox Extensions,” or whether those drawn to “Productivity” really are Scrooge-like, aren't claims anyone should make by citing this graph.

Nevertheless, many of these relationships are, prima facie, meaningful, including every pair in the list of most positive correlations. That the same person would be interested in both “Augmented Reality” and “Wearables,” or “Snapchat” and “Twitter,” needs no further explanation, because it maps to an apparent reality of how tastes relate to one another.

Our argument is simply this: The opposition between “Productivity” and “Games” — that a Hunter who promotes games and a Hunter who promotes productivity tools is less likely to be the same person than for any other pair of interests on Product Hunt — not only maps to an apparent reality, but also to a broader critique of Silicon Valley and its framework of value, time, and experience.

Let's now step away from the data and examine our two personas — one drawn to productivity apps, and the other to games. We'll call the first the nihilist, and the second the gamer.

The nihilist

Summary: The nihilist is not everyone who uses productivity tools, but the person who sees these tools as ends in and of themselves, and for whom the disciplined use of such tools corresponds with the opposite of their stated purpose — i.e., the absence of producing much of anything at all. The world of the nihilist is a kluge of productivity apps that tumorously agglomerate Akira-like in both the nihilist’s organization and individual life. The nihilist’s goal is to project a hologram of value in order to deceive everyone, from peers to managers to investors to the nihilist themself, that something valuable is actually taking place.

In 2018, Judy Wajcman, a professor of sociology at the London School of Economics, published a paper based on her interviews with electronic calendar designers in the Bay Area. Titled "How Silicon Valley sets time", the paper drew a continuum from Frederick Winslow Taylor's scientific management of the early 20th Century — in which Taylor pioneered the practice of timing employees performing tasks down to the second to more efficiently orchestrate their actions — to electronic calendars in the 21st, situating both as nodes in the development of capitalistic time optimization.

From an academic perspective, all predictable enough so far. But what makes Wajcman's paper so useful are the details of this historical continuum, as well as the preoccupations and values expressed by her interviewees:

"In response to my query about why they were working on calendar products, many of my interviewees immediately told me about their own, personal quest for efficient time management. They expressed pride in the way they optimize time, which was a crucial part of their self-presentation and linked to an optimal self. Indeed, their commitment to improving the functionality of calendars seemed, at least in part, driven by their own need for a better calendar.”

It's important to state this explicitly: The explosion of productivity apps on Product Hunt cannot be separated from the personal interests and self-identities of their designers, whose own focus on productivity exists in service of developing other apps for productivity, a feedback loop in which the only thing being optimized is the means of optimization itself.

Wajcman pinpoints the introduction of an application called Agenda in 1988 as a key node in the development of electronic time management. "The aim…was to develop a ‘Personal Information Manager’," she writes. “It was a new generation of software, developed in line with the dream, as old as computing itself, that computers could be used to master tides of information. Indeed, it came to be described as a ‘spreadsheet for words’....to build a comprehensive ‘interpersonal information manager’ that would end the silos between emails/tasks/appointments/notes/addresses, but also between music/photos/blogs…and make this all secure and shared.” (Emphasis added.)

Those who have paid even passing attention to modern productivity software will recognize the language and aim of Agenda, a project from more than 30 years ago, and therefore the broad endeavor of saving time, breaking silos, and endlessly iterating on what essentially amounts to the same few products, over and over, decade after decade.

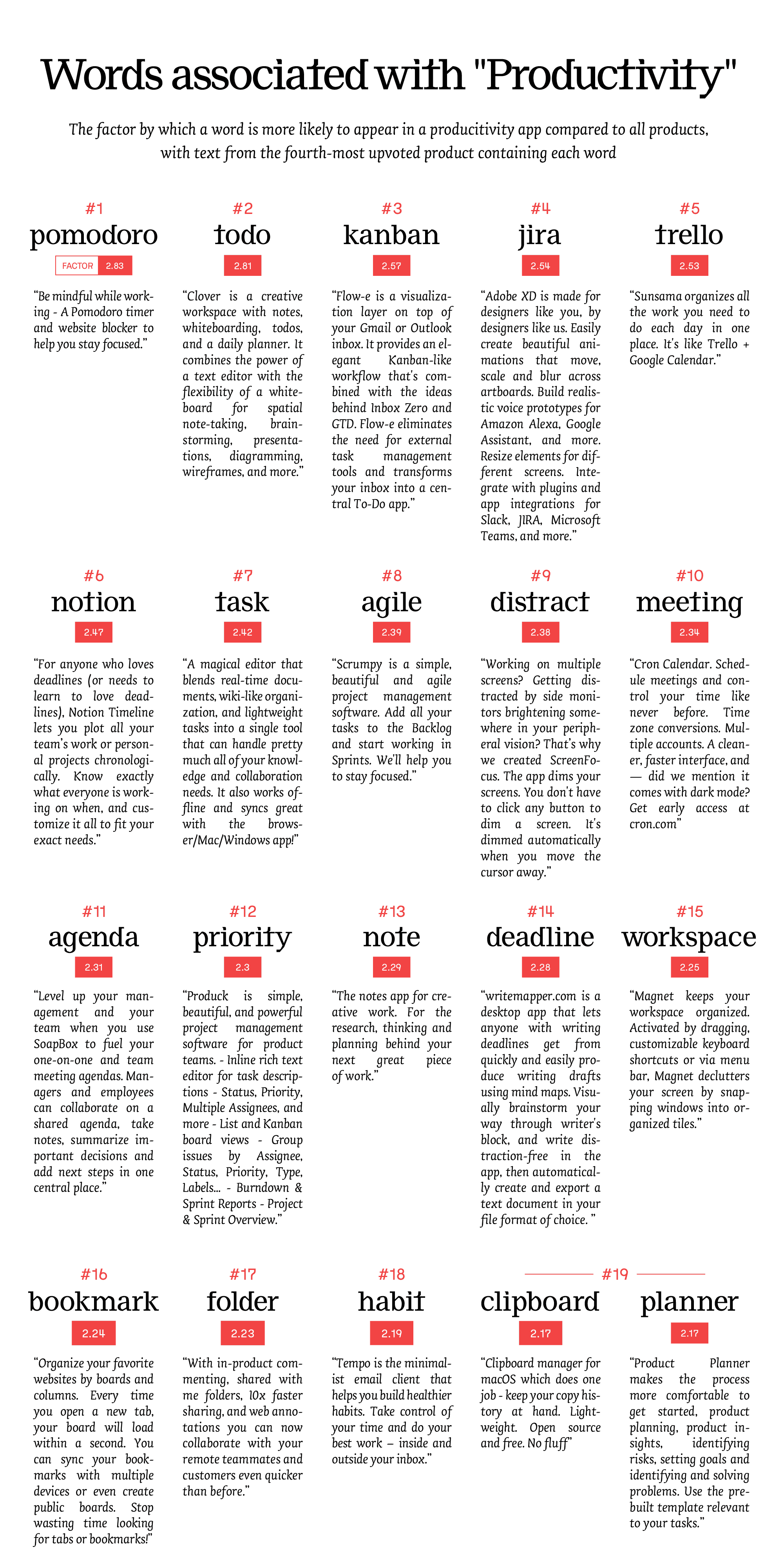

In fact, one sees all of these features emerge when examining the words that define the "Productivity" tag in Product Hunt. Looking at the terms that are more likely to occur in listings for "Productivity" products than any other type, we can see what productivity broadly signifies: The minimization of wasted time, and the optimization of other tools.

Of course, this expanding superabundance of productivity tools is accompanied by a handful of paradoxes. The first is that, as Wajcman observed of her interviewees, the job of dutifully organizing one's own calendar (and by extension, administering most kinds of software-based productivity regimens) "becomes a new task in itself, a form of skilled labour or competency that must be cultivated." Importantly, this task is not simply a minor adjunct to one's primary activities whose net gain is easily identifiable. Instead, "[a]s one of the designers I interviewed, who writes a blog advising people on how to hone their calendaring practice, told me (without irony), he actually spends quite a lot of time doing this work.”

This irony operates on an organizational level as well. According to one survey, the average company now has over 200 app licenses, only 45% of which are ever used. The sheer quantity of apps available in the workplace proliferates to such a degree that they ultimately necessitate their own management team and become a source of confusion for actual employees, whose attention is splintered between three messaging apps, seven spreadsheet apps, and four project management apps. This cancerous spread inevitably becomes the rationale for the adoption of an umbrella app, which promises to unify and integrate the functions of all the other apps within a single piece of software, and which it almost always fails to do.

Second, it's unclear whether making all these apps available to employees has measurably improved productivity on any macro level. On the contrary, the more convincing evidence is that measurable labor productivity hasn’t notably increased since 1970. The picture looks worse the closer you zoom in: Between 2010 and 2018, labor productivity grew by an annual rate of less than one percent, even as the development of these apps ascended to a yet unrealized zenith.

Third, the amount of work whose purpose is nearly impossible to discern has reached an astronomical level. This landscape of meaningless labor formed the premise of David Graeber's landmark 2013 essay "On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs," in which he argued that "Huge swathes of people, in Europe and North America in particular, spend their entire working lives performing tasks they secretly believe do not really need to be performed. The moral and spiritual damage that comes from this situation is profound. It is a scar across our collective soul. Yet virtually no one talks about it."

The wide ranging response to Graeber's thesis (spanning everyone from those who took the highest umbrage to others who felt they were reading a line-by-line account of their own lives) included two surveys, one by the British polling agency YouGov, and the other by a Dutch firm. The results of the two surveys were strikingly similar: Of the employed, 37 percent of Brits believed their work made "no meaningful contribution to the world," and 40 percent of Netherlanders believed, even more pertinently to our current analysis, that their jobs had no reason to even exist — that they could not fathom how their employment aided their organization's production of anything.

Most startup managers would of course consider themselves exempt from such assessments; there's no data readily available indicating that employees within them are more or less useless than those at any other type of company. From collective anecdotal experience, startups are plagued by bullshit jobs at least at the same magnitude as any other category of firm, a reality borne out by the inevitable hiring spree undertaken by most startups after large funding rounds, and the emphasis on headcount as a meaningful measure of a company's success.

Given all of this, the question is why, amidst a broader context of such glaring unproductivity, Silicon Valley's treatment of productivity has taken on what one of Wajcman's interviewees described as a nearly religious imperative, and why it has come to dominate the descriptions of products on the internet's most prominent clearinghouse of new software? Why is so much money (in investment capital for productivity apps, in individual and corporate licenses to use them) and personal time poured into an area whose ability to boost actual productivity is either negative or negligible?

The answer formed Graeber’s thesis, and is obvious to anyone whose life doesn’t depend on not seeing it: actual productivity isn’t the objective. Instead, the objective is the feeling of busyness, regardless of whether that busyness is connected to the production of anything at all. This optimization of nothing beyond the sensation of working hard comes in different forms for different actors, but it sits at the nexus of Silicon Valley's conception of productivity.

To the Veblenian Entrepreneur — a breed of aspirant startup founder for whom, according to the researchers who coined the concept, "entrepreneurship [is] an activity, defined by symbolic manipulation, tokenism and consumption" — using productivity apps is one in a number of cargo cult rituals practiced to secure an entrepreneurial identity. In fact, Product Hunt itself, which offers a subscription program for aspiring founders "to kickstart your startup," fits squarely within the researchers' characterization of the "Entrepreneurship Industry," a market of goods and services that caters to the Veblenian Entrepreneur and ultimately contributes to "an economy that outwardly appears dynamic and entrepreneurial, but is rife with inefficiencies and lacks substantive innovative capacity."

For the middle manager, busy-work is usually done in service to some performance indicator whose relation to the core business and its ability to profit is ambiguous at best and more often simply nonexistent. In a Harvard Business Review article that recast middle managers as “connecting leaders,” the researcher Zahira Jaser wrote that their performance depended on practices like “empathizing with both sides” and “speaking up for others.” Put in simpler terms, the middle manager’s job is to fill up their chosen calendar and task management apps as much as possible.

From the perspective of VCs, the ultimate objective is not productivity as dictated by conventional market logic (i.e., the minimization of costs and the maximization of profits on goods and services), but the shuffling of money between investors, facilitated through the aggregation of various narrative components — branding, headcount increases, a mythos of disruption — until the investment position has grown enough to be worth cashing out through acquisition or IPO. This understanding of the startup economy was lucidly framed in one of the most potent scenes from the series Silicon Valley, a show that tech mandarins routinely claim to enjoy but whose deep critiques they inevitably seem to reject.

In a sector of the economy where "it's not about how much you earn, but about how much you're worth," the labors of the companies whose workflows are built on the kinds of productivity apps that today comprise nearly 40 percent of Product Hunt's output are not actually directed at the creation of a thing, but at the appearance of the creation of a thing.

This detachment between productive-like behavior and actual productivity is why the runaway expansion of apps throughout organizations rarely prompts a reevaluation of their usage, but instead initiates the adoption of yet another super app to solve the problem. The company that conducted the survey mentioned above on the proliferation of SaaS apps was founded to capitalize on this overabundance: Its name is Productiv, it has raised $73 million, and it sells a "software-as-a-service management platform," a category one Gartner analyst called "a growing but early-stage market."

The gamer

Summary: Unlike the nihilist, whose strictures forbid the very idea of wasted time, the gamer centralizes waste (i.e., non-productive activity) as the essence of life's meaning, and therefore as the foundation of value. Accordingly, contrary to the nihilist (who destroys value in their attempt to reduce waste), the gamer is a value maximizer, for the simple reason that they want to minimize the time spent on productive activity and maximize the time spent playing games. This basic arithmetic leads to a straightforward result that avoids the nihilist’s Mobius strip of endlessly optimizing the optimizations, which as we’ve seen, leads to completely nonoptimal systems. The gamer sees ends as ends, and means as means.

In The Accursed Share, George Bataille introduced "general economy," his theory of understanding economies as systems organized primarily for non-utilitarian goods. While day-to-day exchanges — getting your car serviced, buying widgets, etc. — may appear utilitarian up close, at a distance, the broader, general economy ultimately serves non-utilitarian ends. That's because the excess generated by this economic activity can't be reabsorbed for continued expansion — the mechanic can't further expand their shop, the widget maker can't increase their widget production, and so on, resulting in money that has no place to go. This excess is waste, the accursed share which Bataille defined as wealth, and is ultimately directed to unproductive expenditures, like "games, spectacles, arts, and perverse [non-reproductive] sexual activity" — as well as, in his ethnographic reading, war and human sacrifice. In short, the waste is directed towards those things which "have no end beyond themselves."

To Bataille, this waste isn't merely economic — it comprises our very cosmic order, as the sun radiates its waste energy and provides the earth with life. "Beyond our immediate ends, man's activity in fact pursues the useless and infinite fulfillment of the universe,” he wrote. To place waste — which "must be spent, willingly or not, gloriously or catastrophically” — at the center of economics is therefore required not only to accurately depict the function of economies, but of life's very meaning.

The tension between utilitarian and non-utilitarian understandings of both economics and the universe found its way into Graeber's work as well, who specifically considered fun as one possible aim of life's useless fulfillment. After considering the types of theories proposed by rationalist evolutionary biologists who evaluate all behavior for their capacity to maximize survival, Graeber — drawing a line through the random movements of subatomic particles, the observed behavior of ants playing, and human predilection for fun — roughly proposed a different interpretation in the fashion of Bataille:

Let us imagine a principle. Call it a…principle of ludic freedom. Let us imagine it to hold that the free exercise of an entity’s most complex powers or capacities will, under certain circumstances at least, tend to become an end in itself. It would obviously not be the only principle active in nature. Others pull other ways… [S]uch a perspective is at least as plausible as the weirdly inconsistent speculations that currently pass for orthodoxy, in which a mindless, robotic universe suddenly produces poets and philosophers out of nowhere.

The Graebarian construction, then, gives us at least one polarity — fun at one end, bullshit at the other — similar to that which emerges in our data. On either end of this polarity, there is the person who centers experience (particularly the fun kind) as an end in and of itself, and there is the person who centers something else, like optimization for its own sake. And if the universe is calibrated precisely to generate seemingly useless experiences from its excesses, then the person who centers productivity has instead centered something meaningless.

In this sense, the gamer does not only include those who play video games (nor does it necessarily include all those who do). The gamer is a synecdoche; skateboarders, people who seriously play sports, interested music listeners, cinephiles, chess players, big wave surfers, and anyone else who orients their lives towards experiences that contain fun as a major ingredient are all subsumed into the persona. Casually playing a game on a subway or after a busy day to unwind doesn't by itself garner the gamer moniker, while taking paid vacation time to spend a focused 100 hours on Elden Ring does.

Since the gamer is able to properly identify waste versus productive behavior, these activities are never confused for one another, and they maintain their separation. In the world of the nihilist, this barrier collapses; waste and production have no distinction. Among the many ramifications of this collapse is that the nihilist spends their wasted time in the most un-fun ways possible, performing faux productive activity.

The nihilist is unable to see activities as anything other than means to an end, evaluating all objects for their utility in lubricating some other activity — for example, the use of music solely for exercise, falling asleep, building productivity apps, and so on. Because of this, there is no end, only self-perpetuating means. For the gamer, these objects — music, film, games, etc. — form the basis of any cosmic argument, and experience constitutes the bedrock of their understanding of themselves in relation to everything else.

Perhaps it's because of this very ability to distinguish genuinely productive activity from waste that the gamer's organizations tend to follow a saners business models, one in which companies live or die by what they make, not valuations based on speculative futures. We previously explored this dichotomy in our

on the business models of Bandcamp versus Spotify — the former (which centralizes music as an end in itself) profitable by facilitating straightforward exchanges between producer and consumer, the latter (which has advanced music as little more than a hormone-boosting adjunct to other activities) commanding a market cap of $69 billion at its peak in 2021 despite failing to earn a profit nearly every quarter.The economy of game production has so far remained relatively untouched by venture capital and its valuation-over-value modus operandi. The main exceptions include free-to-play Skinner Box mobile games (which do not constitute experiences so much as anti-experiences) and a few high-profile companies such as Epic and Roblox, both of which attracted VC attention because they are seen by investors as stepping stones to something beyond merely a game. Roblox garnered investment because of its metaverse potential, and therefore its potential as a future monopoly. Epic has attracted $7 billion in investment for the same reason, along with Fortnite's popularity in eSports, a sector VCs have fewer qualms about investing in due to teams' abilities to be leveraged into apparel and content brands. (In fact, Epic only became seen as a company worth investing in upon Fortnite's release ― their output in the 16 years leading up to the game, in which they built and sold the widely used Unreal Engine and developed the mega successful Gears of War franchise, won them seemingly no solicitation from Silicon Valley whatsoever.)

As an example of this sort of leveraging, consider 100 Thieves, an association of eSports teams that has received $120 million in funding from investors including Sequoia and Salesforce founder Marc Benioff. Just before the upswing of Covid, the company released a video tour of its new facility in Los Angeles, the Cash App Compound, including shots of players practicing in the building's Totino's Fortnite Training Room and streamers broadcasting from windowless cinderblock prison cells. In December 2021, the company announced a $60 million Series C round in a video laying out its ambition to build a "Marvel-esque universe" of content creators and its plans for apparel and merch drops. In line with the startup economy, it acknowledged its continued unprofitability in service of exponential growth to become "the most recognized brand in gaming." In the 14-minute video, less than two minutes were spent discussing the company's teams. At present, 100 Thieves' skeletal website functions purely as a direct-to-consumer clothing store; one must dig to find any mention of games at all.

Meanwhile, while every new spreadsheet app will either receive venture funding or disappear from the face of the earth, independent game studios can profitably operate while avoiding venture investment entirely. Examples of established studios are legion, ranging from Hitman maker IO Interactive, which generated $78 million in profit last year, to Paradox, who, according to some napkin math, brought in more than $120 million with their latest release, Crusader Kings III. Indie game studios have also been able to successfully leverage crowdfunding in a way that would be totally alien to the makers of some cloud-based pomodoro timer. The three-person Australian studio Team Cherry got funding for its metroidvania masterwork Hollow Knight via Kickstarter and sold nearly three million copies two years after its 2017 launch. RimWorld, another crowdfunded game released in 2018, is estimated to have grossed over $100 million. (As seen in the earlier graph on Hunter category correlations, our data shows a relationship between affinities for crowdfunding and games. As we noted earlier, not every relationship that shows up is necessarily meaningful, but this one does correspond to a real phenomenon.)

The saner business logic of the gaming industry is connected to a number of distinctions between the organizations of the gamer and the nihilist — notably that, unlike productivity apps whose licenses are usually ordered and paid for by someone completely different from the end user, a gamer is almost always both purchaser and user. The prospect of all but the most spendthrift gamer leaving 55 percent of their purchased libraries completely unplayed is unfathomable.

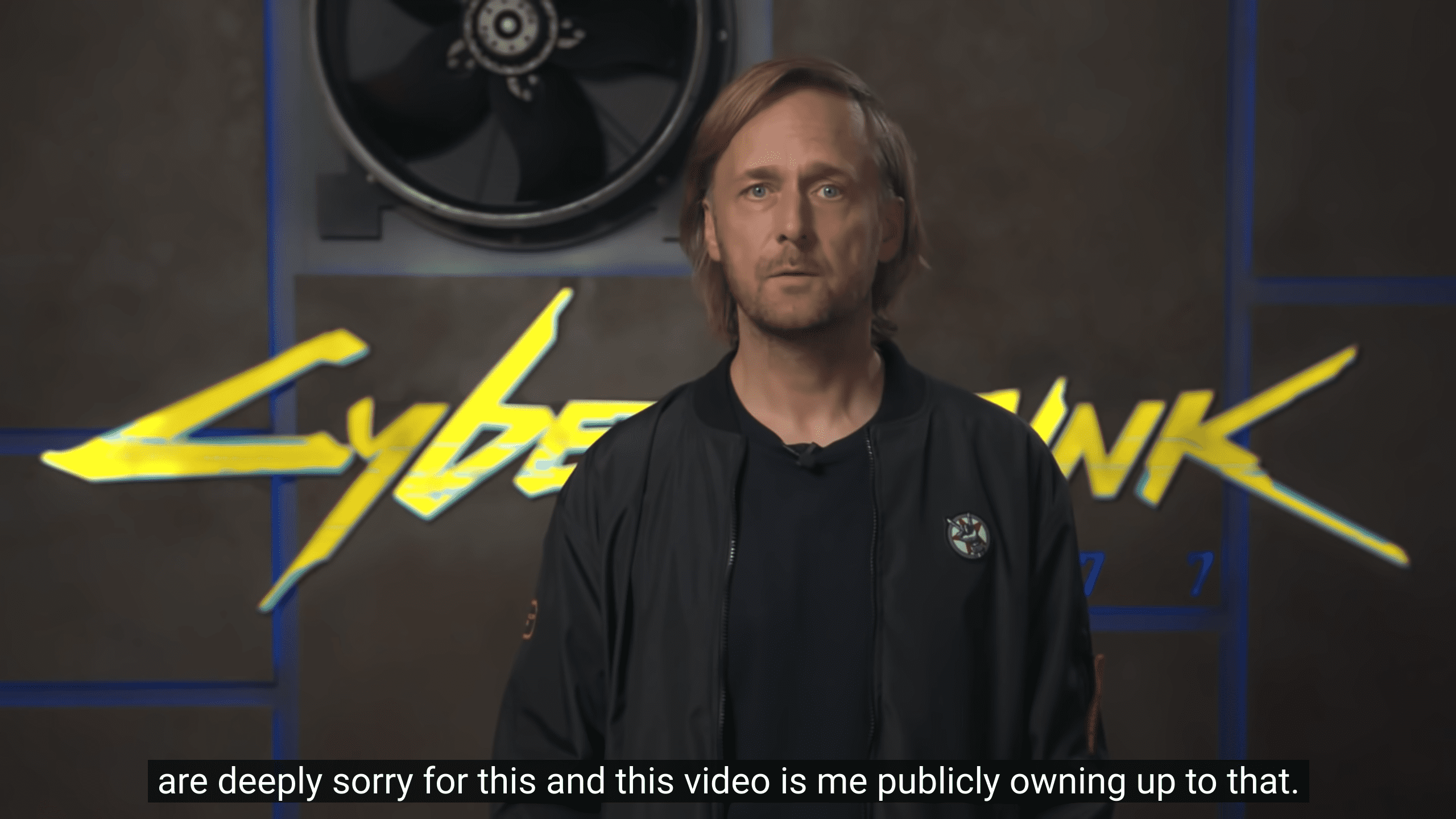

This relates to arguably the most striking difference between their respective organizations: the game studio's greater accountability to its own hype. CD Projekt Red's response to the crisis of Cyberpunk 2077 — in which years of orchestrated anticipation was followed by the release of an 85-percent completed product that didn't function on two major consoles — led to frantic patching and the issuing of mass refunds. Co-founder Marcin Iwiński's apology, when placed next to any non-response of some equivalently dysfunctional AI startup, carried the desperation of an Al-Qaeda hostage video. Bethesda took a similar approach after the bug-ridden release of the also hyped Fallout 76. When players of No Man's Sky complained of an empty, barren universe, the developers overhauled the game to inject its world with new dynamism.

While it is nearly impossible to objectively assess the value that most of Silicon Valley's productivity tools provide to their users, the gamer is able to evaluate goods on a basic, subjective benchmark, one that Blizzard acknowledged in its mea culpa to disappointed players of Warcraft III: Reforged: "We want to say we’re sorry to those of you who didn’t have the experience you wanted."

Nihilism capture

Summary: Attempts by nihilists to govern the gamer's space results in palsied games, with Microsoft and its killing field of studios providing the largest example. The metaverse envisioned by Microsoft, Facebook, and crypto-oriented projects promises game-like systems that are ruled by productivity instead of fun, and functions as a proxy battle between the gamer and the nihilist. So far, gamers themselves have already reacted against these incursions by vehemently denouncing NFTs and forcing developers and marketplaces to exclude them.

What happens when the nihilist encroaches onto the gamer's territory? Perhaps no other company has done so as successfully as Microsoft. In February, the company's CEO, Satya Nadella, justified his mandate to build the nebulous concept known as the metaverse by claiming, "Being great at game building gives us permission to build the next internet."

It is true that Microsoft makes and distributes games, a lineage that runs from the original 1982 Flight Simulator to everything currently related to Xbox, including its pending $75 billion acquisition of Activision Blizzard. It is also true that the way it has handled its gaming division is precisely what one would expect from the creators of Windows.

The YouTube game critic videogamedunkey's 2019 discussion of Microsoft's gaming operation provides a concise but thorough overview of the company's body count when it comes to not only the number but the type of failures it has amassed over the years, which ultimately rendered the Xbox One "the system to get because your friends have Xbox." Microsoft's acquisition of Rare, which in the 1990s created groundbreaking titles like Donkey Kong Country and Banjo Kazooie, ended with the studio "reduced to making shovelware Kinect games," a reference to the Xbox's motion-capture peripheral whose canyon-sized disparity between marketing and reality made it a case study in consumer tech hype. Beyond Rare, Microsoft's acquisition spree of other studios functioned as a Sports Illustrated cover curse, ending the hit-making heydays of each. As Dunkey surmised, "Either these guys just have the shittiest luck ever, or they're not willing to dig deep and spend the money to get stuff made right."

On this last point, Dunkey is probably wrong. Bungie — the studio behind Halo that was acquired in 2000, when it was nearing completion of the game, in order to turn Halo into an Xbox launch title — left Microsoft in 2019. From there, Microsoft's own in-house studio ended up creating Halo Infinite at a cost of $500 million, making it the most expensive game ever created. (The result was a product basically similar to the other titles in the franchise.) And while not every game the company produces carries such a high price tag, there's not necessarily any sign that the studios it acquires are victims of slash-and-burn cost cutting. In fact, games that Microsoft published but didn't actually develop, like Ori and Cuphead, have still been able to achieve both commercial and critical success even with shoestring teams.

Rather than miserliness, Nadella unwittingly pinpointed the problem himself as he made his case for why his company would be the first to build the metaverse. "[In] the Microsoft I grew up in, I always think about three things," he said. "The three things that we always had are: we built tools for people to write software; we built tools for people to drive their personal and organizational productivity; and we built games."

Put another way, Microsoft's track record is the predictable result of combining an organizational culture whose cornerstone ethos is productivity-destroying software and bullshit work with their diametrically fun opposites. And Microsoft offers perhaps the best case scenario of such an equation, which for other tech companies has resulted in a total wash: as the Financial Times noted, "Early attempts by Google and Amazon to create games studios of their own have failed to make a dent."

The company's relentless destruction of game studios aside, the threat to fun posed by a tokenized metaverse, crypto, NFTs, and everything else comprising the fatberg of web3 is, while procedurally different than the gutting of Rare et al., similar in effect.

As far as our Product Hunt data is concerned, the relationships between Hunter tastes between productivity, crypto, and games is fairly inconclusive, with no definitive relationships either way. Observationally speaking, there was no shortage of CS:GO players who went long on Dogecoin during its manic peak. But gamers engaging in a standalone pump-and-dump scheme is categorically different from tokenizing a game itself. The arguments of crypto boosters for their incursion into gaming — which ultimately results in games as utilitarian financial operations rather than meaningful uselessness — relies on the same nihilistic opposition to the gamer's framing of time, and the same refusal to consciously embrace waste as value. This misalignment was articulated by Reddit cofounder and VC Alexis Ohanian, who claimed that, in 2027, "90% of people will not play a game unless they are being valued properly for that time," predicting that play-to-earn crypto games would soon displace every other form.

Because the nihilist is unable to make good games, the output of their efforts so far have made Ohanian's prognosis as bleak as it is unlikely. ("Most of the people who are talking about metaverse have absolutely no idea what they're talking about," Valve president Gabe Newell told PC Gamer. "And they've apparently never played an MMO.") And so far, gamers' reception of crypto into their world has taken on the exact opposite form that Ohanian predicted. Instead, gamers' vehement backlash against NFTs has forced multiple companies to explicitly position themselves against the technology. Among them, Sega dropped its plans to include NFTs in future Sonic games. The indie game store Itch.io issued a condemnation. Valve outright banned NFTs on Steam, the world's largest marketplace for PC games. And even Epic promised it would not integrate them into Fortnite.

One company that admitted it "under-evaluated how strong the backlash could have been" to its NFT rollout was Ubisoft, one of the most commercially successful game studios in the world as well as one of the most reviled. For Ubisoft, NFTs are merely the latest in a nihilistic transformation that has played out over time. In 2018, it released Assassin's Creed Odyssey, a third-person open world action/adventure game with a traditional leveling system based on experience points, which are earned in side quests. Ubisoft offered microtransactions in the game that allowed people to skip the quests entirely and purchase XP with real money "so that you don't have to actually play the game you just bought for $60," as Dunkey put it. The feature was called "Time Savers."

Conclusion

Our argument isn't intended to create a rigid dualism between the gamer and the nihilist, but rather to point out an underappreciated dichotomy. Very few people fall neatly into one camp or the other; many would fall into neither. All sorts of issues arise when actually applying this framework that we won't try to reconcile, such as which heuristic best fits professional athletes, eSports players, Twitch streamers, musicians, and so on, all of whom can blur the line between utility and fun. Similarly, nothing contained in this report should be taken in absolutist terms. Not all productivity tools are vehicles of nothingness (many of them are quite useful), and not all the people who design and fund them are nihilists. What's important is the contemplation of the fun experience as opposed to faux productivity and bullshit work.

While we were preparing this report, the tech economy (including crypto) was suddenly bludgeoned by reality, courtesy of rising interest rates that effectively neutralized the pandemic bubble. The era of easy money is now over, while the price of crypto has crashed along with the stock price of every perennially unprofitable company birthed in the post-2008 tech craze. This contraction will likely have consequences for venture funding and the ability of investors to exit companies via IPO or acquisition as the appetite for risk dries up. Somewhat overnight, the fund-everything, hire-everyone mania that pervaded has been replaced with the cold arithmetic of cash flow.

As money and work ideally become re-oriented towards some vaguely rational idea of value, the opposition between the nihilist and the gamer is important to reflect on in service of injecting sanity, and even some shred of morality, into our markets. In his essay on fun, Graeber summed up Friedrich Schiller's own views on fun, that "it was precisely in play that we find the origins of self-consciousness, and hence freedom, and hence morality. 'Man plays only when he is in the full sense of the word a man…and he is only wholly a Man when he is playing.' If so,… then glimmers of freedom, or even of moral life, begin to appear everywhere around us." For Kant as well, an ability to separate means from ends represented a pillar of the ethical life. And Zeus deemed work without meaning a sentence to be doled out to those deserving of the most intolerable hell.

There is no shortage of kind and good-hearted nihilists, and no shortage of black-hearted gamers. But the respective economies organized around each framework can’t help but tip the moral balance in one direction, however counterintuitive that morality may sometimes appear under RGB lights. As Wajcman said at the end of her paper, "Calendars will never ask us what we want to save time for." Neither will Jira, Monday.com, or any of the other apps built less to optimize than to be optimized. Games at least ask the question, and they can begin to help us form an answer.