Summary

This report is the final piece of research about Bandcamp on Components. It finds that the sale of physical objects is strongly positively associated with the amount of money that artists make on the platform, and that among all types of objects sold, this association is strongest with vinyl records. Additionally, the purchase of physical objects becomes increasingly common among buyers as they spend more money overall, with vinyl alone encompassing more sales than all other physical objects combined. In other words, the format is a disproportionately important channel of spending.

We use this analysis as a starting point to understand the well documented resurgence in vinyl sales across the broader music industry. Rather than signaling a retro craze or an appetite for collectibles, we argue that a commonly cited reason for purchasing vinyl is more important — that the object is "tactile." This tactility is considered in the context of Marshall McLuhan's understanding of the term as the "synesthetic mode of interplay among the senses," a precondition to existing in a space of experience. We draw upon McLuhan's predecessor, the American pragmatist John Dewey, and argue that people's identification of vinyl's tactility ultimately points to the object's potential for what Dewey understood as aesthetic experience, as contrasted with the un-aesthetic gravitational pull exerted by most forms of streaming. As we have argued in prior work, this form of experience possesses irreducible value, and is thus something people pay for.

We further analyze the limitations of overreliance on vinyl as a vessel of this experience, including the affinities between different kinds of music and different formats, and the changing demographics of Bandcamp customers, who increasingly come from countries with lower GDPs and are far less likely to buy vinyl than customers from richer countries.

Components has been analyzing Bandcamp since late 2020, beginning with our

of cities and the various musical genres they spawn. in early 2021 examined the company's business model and raised a simple question, one that has become even more relevant in an economy after easy money: Why is Bandcamp profitable and Spotify not? The answer we arrived at was that Bandcamp provides a simple platform for complex transactions, while Spotify is a technically complicated platform for facilitating a single transaction in the form of the one-size-fits-all subscription.Since the completion of those two projects, we have mostly drifted away from Bandcamp and explored other topics, including the warped framework of

and the nature of true value as in the dichotomy between productivity apps and gaming (a subject of imminent relevance to the present report). But if the original Bandcamp thesis boiled down to "simple business model, complex economics," the consequent question that it invites — what are the features of that complexity? — became more irresistible to try to answer as our cache of data from the platform grew to encompass two-and-a-half years' worth of sales activity, today including more than 50 million sales.This question was also raised last year when we published a small sidebar piece after Epic Games' acquisition of Bandcamp. That piece contained a graph of the top selling artists from February 2022, showing that the highest earner from the month prior was the rapper WestSide Gunn, when he released his album Hitler Wears Hermes (side B). Gunn's revenue in our data for that month came out to a little more than $260,000 (a number more likely to be under rather than overestimated, a caveat of all dollar figures here). But the rapper not only held the distinction as the month's top selling artist — his top ranking was also notable for owing exclusively to the sale of limited edition physical objects, mostly vinyl, a model employed for all his other releases, as well as for all those of his label, Daupe.

Within the entirety of Bandcamp's marketplace, this makes Daupe an anomaly. Artists on Bandcamp almost universally sell digital albums and tracks, with the additional option to purchase physical merch like vinyl, cassette tapes, CDs, and other miscellaneous items like booklets and clothes. From the perspective of Bandcamp's origin — emerging after Radiohead's pay-what-you-want experiment with downloads for In Rainbows — this makes sense. But even in our original report on the company, we found that physical items played an outsized role in the site's revenues: The original figures from late 2020 show that physical items, despite comprising less than a quarter of the actual goods sold on the site, make up about half the revenue it generates.

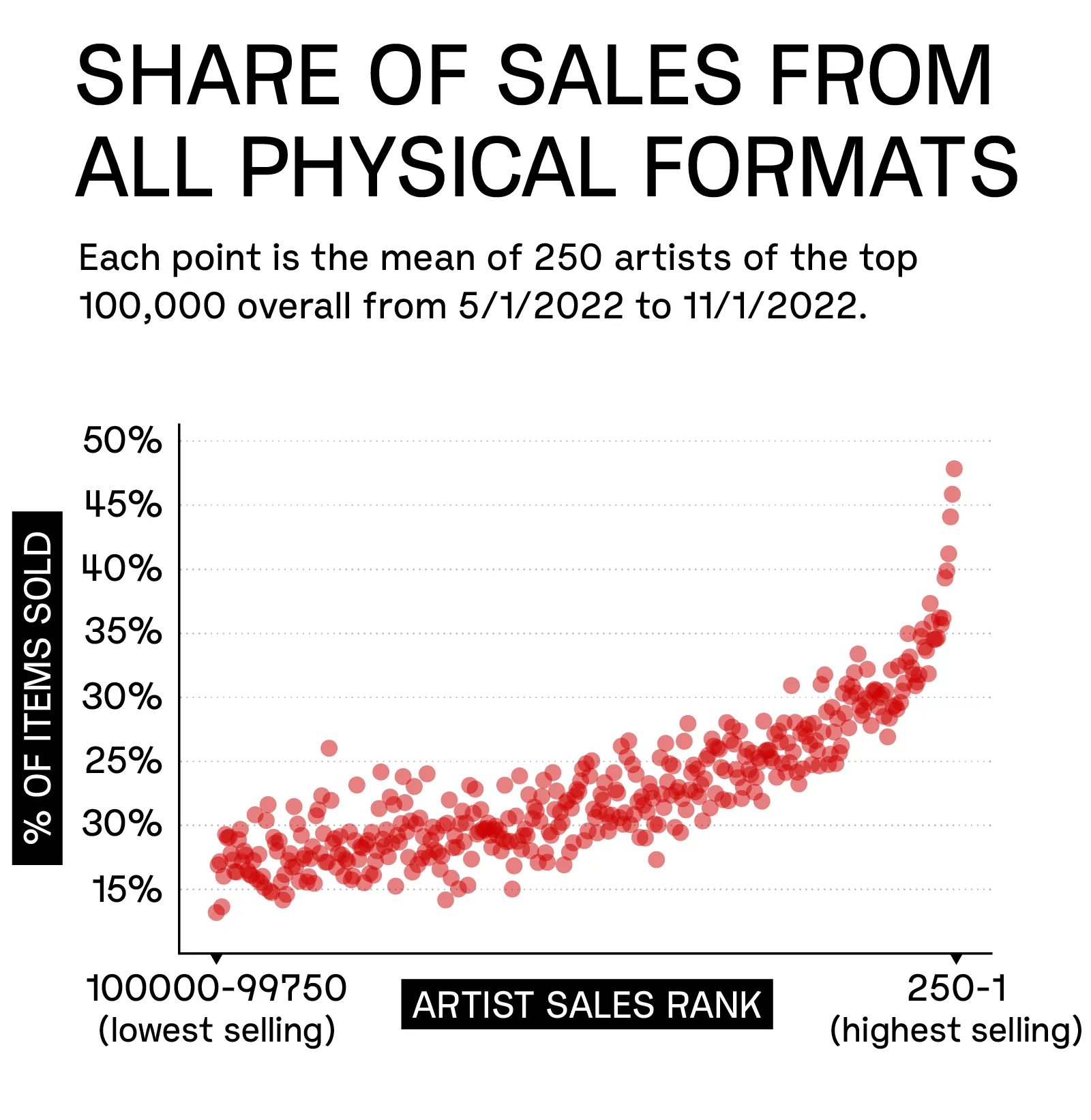

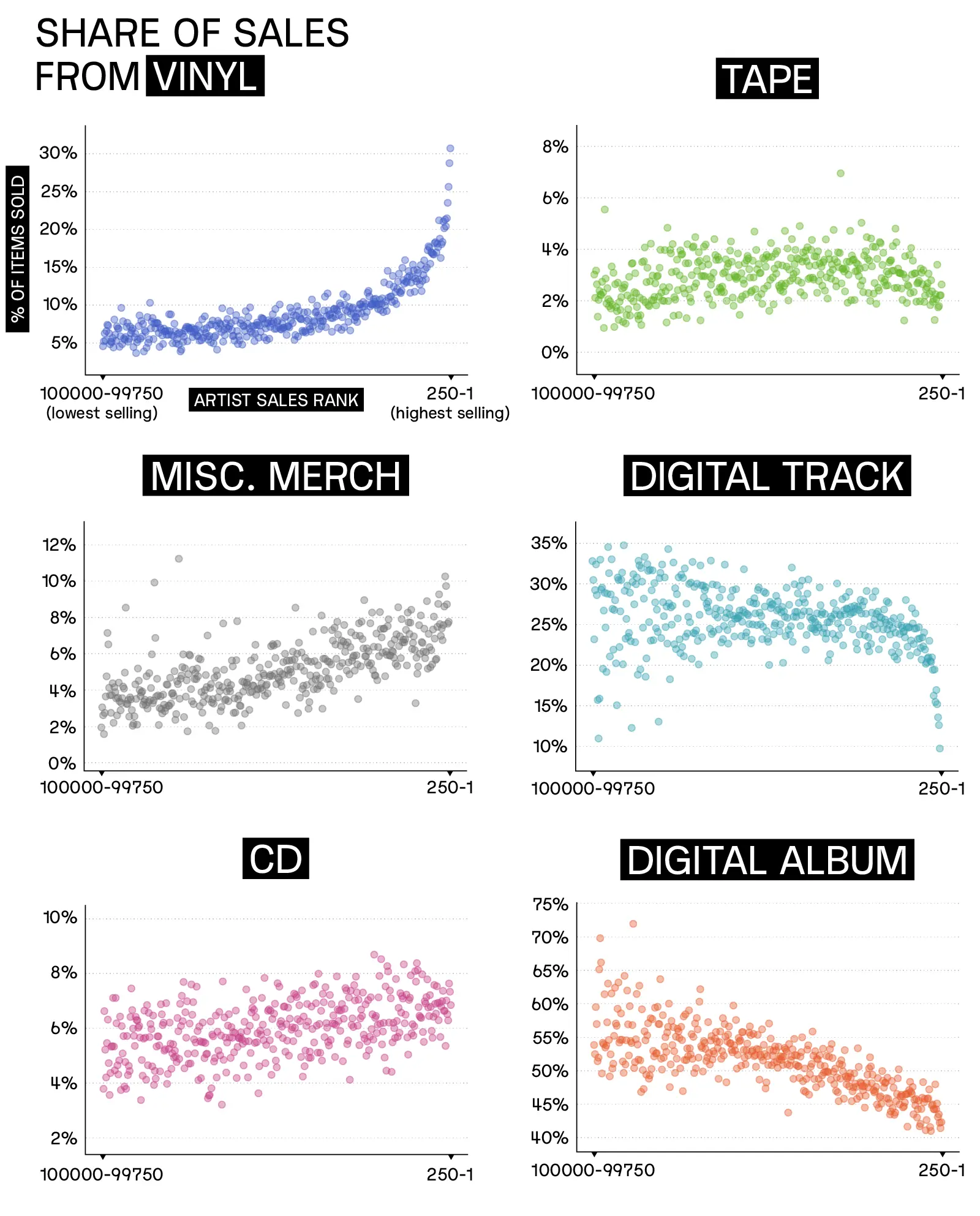

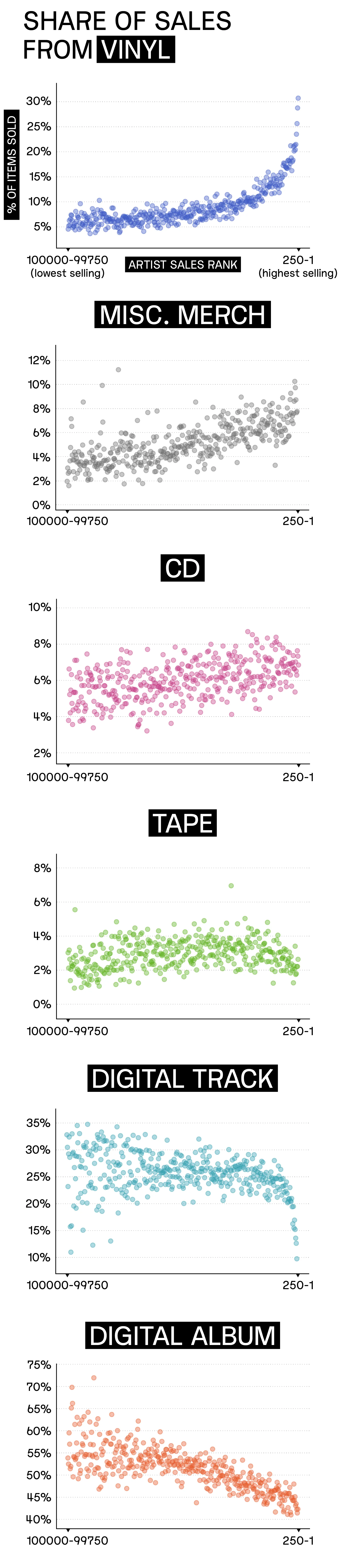

The inference from all this — Gunn's placement among top artists and the disproportionate amount of revenue generated from physical sales sitewide — becomes explicit when looking across all artists on the platform. On balance, the more money an artist makes from selling physical stuff, the more money they make overall, which we've measured by their sales rank.

This relationship is not equal among all objects. While there are positive relationships between artists' sales rankings and CDs and merch, and a mostly positive relationship with ranking and tapes (one that drops off among the highest selling artists), the linkage between sales ranking and vinyl sales is the most stark. In other words, in the simplest and most reductive terms, the artists on Bandcamp who are able to move the most vinyl are the ones likely to make the most money, while those whose sales depend most on digital music end up making the least.

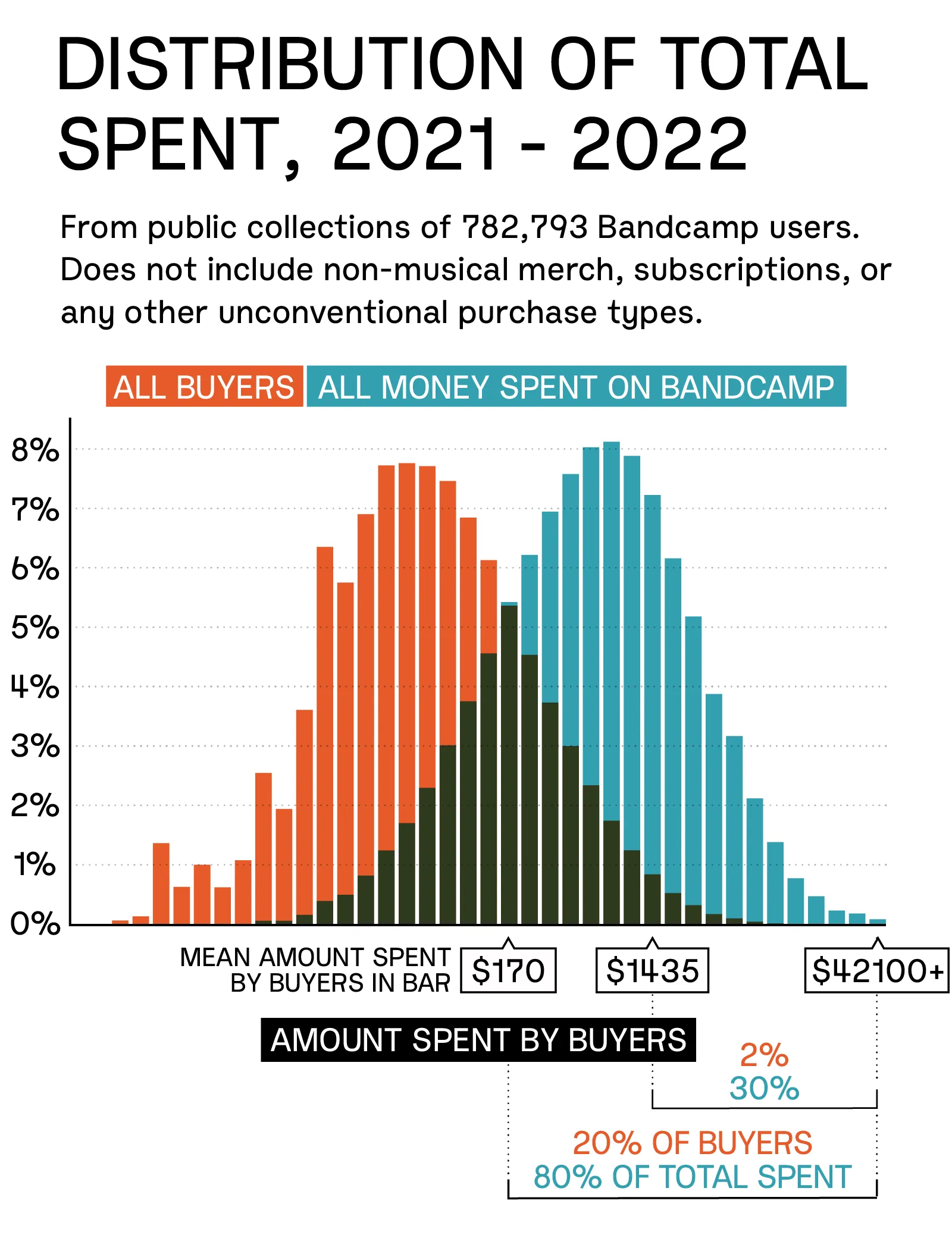

This trend emerges from the buyer's side as well. To demonstrate this, let's first look at the distribution of how buyer spending breaks down across the site. In our first report we surmised, without looking at any publicly available buyer data, that Bandcamp almost certainly benefited from the Pareto Principle, in which 20% of buyers make up 80% of purchases. As it turns out, this distribution plays out pretty much exactly.

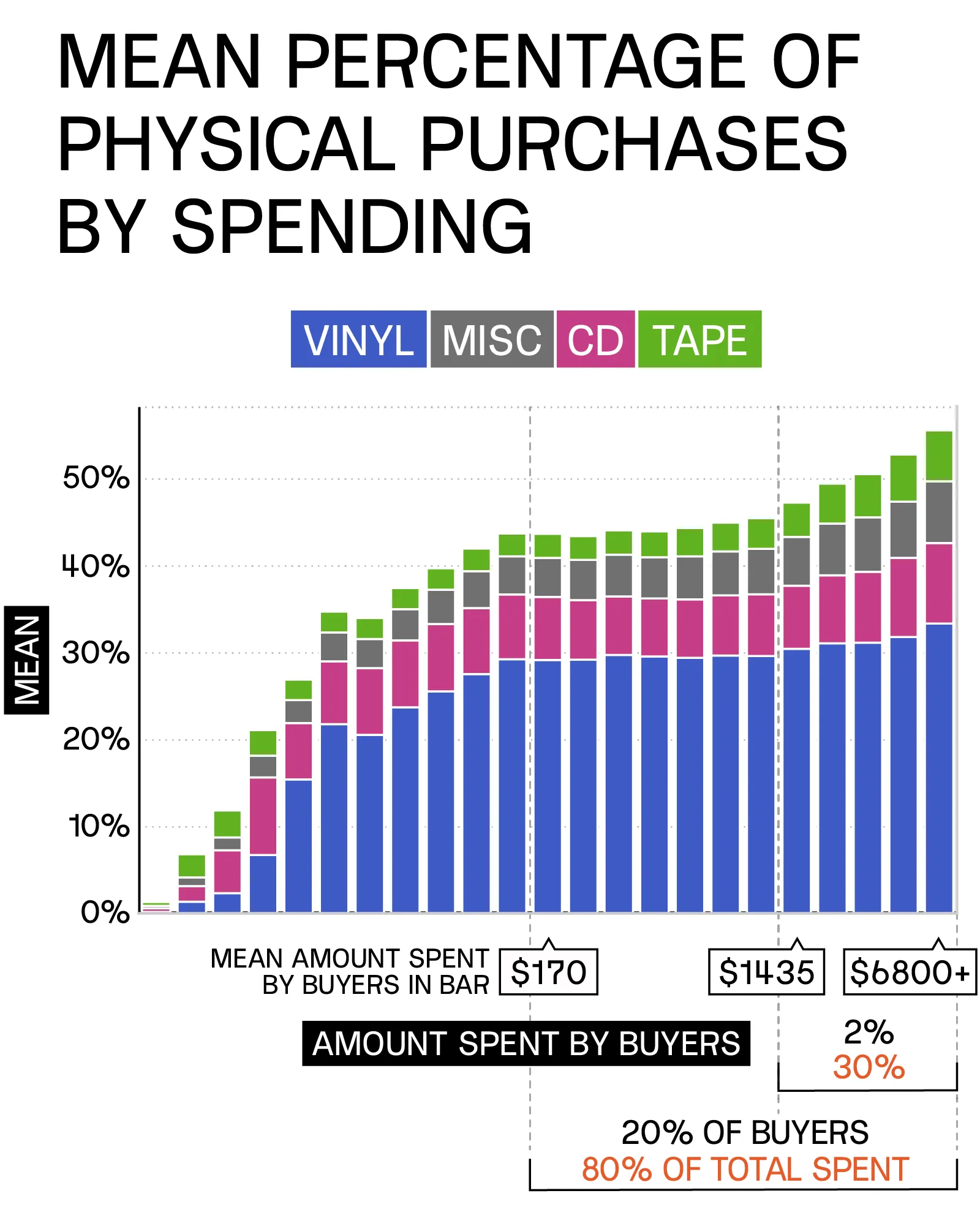

As people spend more money, the share of physical purchases they make keeps climbing. On average, purchases of physical objects by those in the top 20% of buyers generate about 47% of dollars spent in our data, but again, this is certainly an undercount, and the proportions are likely higher.

Why does this particular format channel such a disproportionate amount of money? Sales of vinyl records have been on the rise since 2006, with more than 40 million albums sold last year, generating $1.2 billion in revenue for the music industry, more than double the take from 2019. Though streaming, which represents 80% of the total market, is dominant, vinyl has become the second most popular format for recorded music and been fully reintegrated into the industry's mainstream. Harry Styles sold 480,000 copies of the vinyl edition of Harry’s House in 2022, second only to Taylor Swift, who sold close to a million copies of Midnights. The heightened demand for vinyl from fans of the world’s premier popstars has caused serious supply chain issues as the handful of factories that still press records struggle to keep up, but the market is adjusting, with around a dozen new facilities in the pipeline, including pressing plants in California and England slated to open this year.

The causes for the resurgence of vinyl have been pored over so thoroughly that one can now sift through them to find any justification they want. Some emphasize the format's sound quality, a position that others argue has little objective merit. Some identify the collectibility of records, others the nostalgic reprieve of the retro in a world whose pace towards an ambiguous, technologized future only seems to accelerate. Some point to the item's inherent scarcity, particularly with limited edition presses like those sold by Westisde Gunn, an interpretation that suggests an appetite for the digitization of the object's essence in the form of NFTs. The collapse of the NFT market amid the steady growth of vinyl sales not only falsifies this explanation, but demonstrates the hazards of the wrong interpretation.

But one concept is raised so regularly in the discussion that it effectively sits at the center of the format's discourse, a quality that seemingly no one disputes. As one college student expressed in 2021 when explaining their affinity for vinyl, "I’m using streaming basically 24/7, but having records has been a way of making my favorite music tactile."

When Steve Jobs introduced the iPhone in 2007, he began his pitch of the device's capabilities with a seemingly novel feature: "You can touch your music,” he said with palpable glee. “You can just touch your music. It's so cool."What Jobs literally meant was that iPhones had touchscreens, songs on the iTunes store came with album art, and you navigated between these songs with your finger by touching the pictures.

But Jobs's delivery is notable for two reasons. First, his giddiness, even if marketing affect, demonstrates that it would be incredible to touch your music — the hitherto untouchable — so much so that it might prompt you to buy a first gen iPhone. Second, and more importantly, this very ability reaches its nadir with the device's cultural saturation.

When people say they value vinyl's tactility, when Jobs expresses delight at the idea of touching music — what does this actually refer to? More importantly, why is this valuable?

To Marshall McLuhan, tactility was a core concept in the glossary that defined his often bewildering approach in the 1960s to understanding the rise of electronic formats like television. McLuhan framed tactility as more complex than mere physical touch. Instead, it was “that very interplay of the senses which we call synesthesia," a description he deployed variously and repeatedly throughout his work. To McLuhan, tactility involved "a fruitful meeting of the senses, of sight translated into sound and sound into movement, and taste and smell."

If this sounds a lot like how we experience the world — playing a baseball game or eating a plum or anything else — that's because it is, and the default mode of living is one that is basically tactile. But this then begs the question of what isn't tactile. Aren't we always mixing up our senses? If we're not, what exactly are we doing?

McLuhan's answer was that we don't do this in what he called "visual space," which was characterized by rationalistic thought processes and media, most notably print, which he asserted amputates the complex interplay of our senses at the expense of one, the "visual", and sands away the tactility with which we had traditionally lived until the arrival of the Gutenberg Press. In this formulation, print reduced our experience of the world to mere alphanumeric characters and logical thought patterns, which could be approached only in a linear, mechanical fashion. This form of engagement, he argued, was the antithesis of both traditional oral communication that had characterized humanity for thousands of years — which involved musicality, the movement of human gestures, and orientation in a physical place — and human nature itself. The result, he argued, is "a ditto device."

This notion of reducing the senses can be alien on first encounter, so let's use an example. Let's say you wind up in Center City, Philadelphia. You're at 20th and Sansom Streets. It's 90 degrees outside, but amid the defoliated environment of the city, it feels like 105. You are standing on an intersection that has it all: On the southwest corner, a Shake Shack is foregrounded by a can overflowing with so much garbage that it can be seen from all the way down the block. On the southeast corner, the erection of a soulless glass luxury condo building that has dominated the entire block continues into its 10th year, soundtracked by endless construction noise. On the northeast corner, you see a VC-backed app-based pharmacy with copypasta localized branding ("Hello, Philadelphia"), and on the other, a gourmand eatery selling $30 veggie burgers. A completely spotless, full cab F-150 with a covered bed (never uncovered) and a Blue Lives Matter window decal drives by. You recall that Martin Luther believed we live in hell. You know now that he was right.

McLuhan's assertion is that the words used to describe this event will never actually transmit the experience, because the experience itself involves more than merely the eye. Instead, it utilizes the entirety of our sensorium, and that by forcing the experience into "visual space", it is reduced to a mere unfelt set of symbols — a form of non-experience.

As the physicist and media scholar Robert Logan (whose tenure at the University of Toronto coincided with McLuhan's) summarized it, "The perceptual bias of visual space is linear, sequential, rational, fragmented, causal…and specialized." On the other hand, what McLuhan dubbed the "acoustic space" that defines our natural interaction with the world is "simultaneous,...intuitive, all embracing, mystical, inductive, and experiential," and is at its basis a space of tactility, of the senses working together to create a gestalt that is more than just the sum of its parts.

This might seem somehow both hopelessly abstract and brutally literal at the same time. Does all this simply mean that watching a movie is tactile but looking at a painting isn't? But why would McLuhan specifically cite "the tactile interplay of the senses which painters since Cézanne had stressed as needful" if a painting is a form of visual art? Can't good writing do the same thing?

The answer McLuhan alluded to was that this tactility is maintained when the content corresponds to a prior synesthesia:

A sphere, for instance, appears to the eye as a flat disk; it is touch which informs us of the properties of space and form. Any attempt on the part of the artist to eliminate this knowledge is futile, for without it he would not perceive the world at all. His task is, on the contrary, to compensate for the absence of movement in his work by clarifying his image and thus conveying not only visual sensations but also those memories of touch which enable us to reconstitute the three-dimensional form in our minds.

The tactility of Cézanne's work, therefore, resulted from his ability to evoke the synesthesia involved in a sense of being. One enters the sensorial cavern of the artist’s mind when looking at one of his still lifes, sharing what he experienced on a cognitive level. One sees the painting with more than just their eyes.

The challenge becomes that spending too much time with McLuhan results in a labyrinth of complications and contradictions; as one writer put it, a chief pitfall when dealing with McLuhan is absorbing him "without a great deal of mastication and, if necessary (and it's often necessary), regurgitation." So let's chew up and spit out a few things. What ultimately matters can be reduced to a few broad strokes:

First, let's completely ditch the confusing terms "acoustic space" and "visual space" in favor of "tactile space" and "non-tactile space." Second, let's further say that at the basis of everything in this tactile space are the dynamics of raw experience. And lastly, let's assume that when people say they value vinyl for its tactility, they are situating both the object and their engagement with it somewhere within this realm of experience. In doing so as a flight away from streaming, they are placing streaming somewhere amid a place of non-experience.

This raises a new ambiguity: what is "experience"? To better try to understand what exactly is happening here, let's step back to an important McLuhan forbearer, the most important American philosopher, and the patron saint of this website, John Dewey.

McLuhan described Dewey as "surf-boarding along on the new electronic wave," despite Dewey working in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. The Medium is the Massage — McLuhan's attempt at creating a quasi-interactive, graphic-centric book that shunned linearity — includes a Dewey quote printed backwards that one must either hold up to a mirror or painstakingly decipher:

Compartmentalization of occupations and interests brings about separation of that mode of activity commonly called "practice" from insight, of imagination from executive doing, of significant purpose from work, of emotion from thought and doing. Each of these has, too, its own place in which it must abide. Those who write the anatomy of experience then suppose that these divisions inhere in the very constitution of human nature.

What exactly does this mean? Dewey argued that humans, like all living organisms, operate in the world through the synchronous operation of our sense organs. Our interactions with our environment are so inseparable to our being that in many ways, we are inseparable from the environment itself. This uninterruptible exchange between the environment and our bodies forms reality. By "experience," then, Dewey referred to this active participation in our environments.

Dewey believed that the dulling of the exchange with our environments wrought by compartmentalization defined the modernist malaise. This cause and effect can be observed at every level, no matter how far out or close in you zoom. The division "of occupations and interests" manifests in the artificial barrier with which we treat, say, physics and literature, since each is merely a different angle from which to understand an indissoluble whole (i.e., the entire cosmos). A macro, spatial example would be sprawling, rationalistic exurban developments with rigidly demarcated land uses that detach us from our surroundings and our society, shorn of the various types of mixture needed for both society to properly operate, and for us to fully experience anything.

According to Dewey, these divisions are absent in childhood — our natural impulse is to mix things up and explore their contours from all angles. In a line later echoed by McLuhan above, he describes "the joy the child shows in learning to use his limbs, to translate what he sees into what he handles, to connect sounds with sights, sights with taste and touch" — the infantile instinct for synesthesia and the tactile space.

The artificial separations that define modern life, Dewey said, begin with the reduction of education to rote memorization rather than playful experimentalism, which he viewed as a fundamentally anti-democratic affront to human nature. Dewey argued that education in its non-experiential form — in which knowledge flows unidirectionally from teacher to student, instead of being discovered by the student through exchange with the environment — is a practice of emotionless, brute force information transfer without any demonstrable relevance to the student's world, and that it fails to foster the curiosity he deemed the hallmark of true intelligence. It is essentially a world in which people learn everything about baseball without ever playing or watching a game, where they draw spheres without ever having felt one. When an ornery teen provokes their math teacher to explain why they really need to learn Algebra 2 in the first place, they are in fact throwing down a gauntlet that Dewey believed was of the highest philosophical and moral importance.

Because this information doesn't adhere to experience, we end up with McLuhan's "ditto device" — information can be repeated but never re-interpreted, because it is never actually felt from the unique vantage of an individual. (This is how we end up with "bodies and spaces" played on repeat). Among the figures produced by this model is what the French sociologist Pierre Bordieu called "the pedant who understands without feeling," and whose paragon is Patrick Bateman, the high-achieving murderous narrator of American Psycho. A recurring symbol in the novel is a painting that Bateman owns and talks about to display his taste. At one point, Bateman struggles at a dinner party to demonstrate his personal knowledge of why the painting even matters:

"Well, I think his work... it has a kind of... wonderfully proportioned, purposefully mock-superficial quality." I pause, then, trying to remember a line from a review I saw in New York magazine: "Purposefully mock..."

Bateman's glitch represents the unfelt second-hand relationship to the world that emerges from a mode of non-experience, an "understanding without feeling" that momentarily fails. The painting functions as an expository prompt, not as a conduit of experience through which his own reaction would emerge spontaneously. It is this same character who describes his nihilism in detail towards the end of the novel, and who confesses, "My pain is constant and sharp."

It is the contention of this project that behind the continued surge in vinyl sales is a sense of relief from a pain that, if not always sharp, is nearly constant, borne of a nihilistic non-experience that has become even more pervasive under the regime of Silicon Valley. People feel this pain whether they know it or not. But to draw out this assertion, we need to pass through one last Deweyan idea: the concept of "aesthetic experience."

If "experience" writ large is the ongoing exchange between ourselves and our environments, then "an experience" is when this engagement is demarcated by a beginning and an end. To Dewey, these experiences are aesthetic when they take shape, accumulate, and ultimately consummate — when their different elements build upon one another and refer to each other, and in doing so, imbue each element with meaning. In this sense, a logger chopping down a tree, an electrician fixing a house's wiring, two people engaged in a conversation, or even a bird building a nest bears no essential formal difference from the work of a painter or a musician, since in all cases, the basic dynamic is the same: In each of them, the elements of the experience bind together "into a single whole," and their "varied parts are linked to one another, and do not merely succeed one another."

This single whole is also bound together by an emotional current. Dewey gives the example of a person setting out to clean their room: Performed as an automatic habit with little conscious thought, the experience is not aesthetic in nature. But when propelled by a mental charge — like a sudden need to impose a sense of order on one's life, or amid a drug binge — the experience becomes emotionally unified.

Art, then, reflects this form of experience, and is experience, just as experience itself is essentially art (hence the title of Dewey’s treatment of the subject, Art as Experience). To Dewey, art involves a series of experiential steps. The artwork begins through primary experience, like a painter experiencing a field or a musician experiencing the DMV. This is followed by the artist embodying that experience into "aesthetic form," like a painting, a song, etc. The audience of this work then has their own aesthetic experience of the work, in that as they see/hear/read it, each part builds upon what came before and what will come after (in this sense, Dewey believed all art was temporal, including forms like photographs, as one engages with the work's different elements over a period of time that are not all at once apparent). Dewey gives the example of Hamlet's last words, "The rest is silence": taken on their own, the words mean nothing, but seen in the context of the rest of the play, they are not only imbued with meaning, but imbue everything else that came before them with new meaning as well. "In a work of art," he wrote, just as in aesthetic experience itself, "different acts, episodes, occurrences melt and fuse into unity."

Dewey contrasted this with what he called (in his archaic spelling) "non-esthetic" or "anesthetic" experiences, which he described as having "slackness of loose ends" marked by "deviations in the opposite directions from the unity of experience":

Things happen, but they are neither definitely included nor decisively excluded; we drift. We yield according to external pressure, or evade and compromise. There are beginnings and cessations, but no genuine initiations and concludings. One thing replaces another, but does not absorb it and carry it on. There is experience, but so slack and discursive that it is not an experience. Needless to say, such experiences are anesthetic.

This is our argument:

The tactility people identify in records is not simply an acknowledgement of the object's raw physicality, but of the object's experiential, and ultimately aesthetic, nature. This occurs on two levels. The first involves playing the record itself: A person begins with a mental charge to play a record, they walk to where the record is, they pull it out of its sleeve, they put it on the turntable, the turntable plays the record, and then the record eventually stops — an initiation and a concluding involving one's physical environment. In between this initiation and concluding, something happens, whether that is actively listening to the music, mopping the floor, or having a conversation. In other words, there is the aesthetic experience of the music itself, and there is the aesthetic structure of experience molded by the listener's intentional initiation of that music in the environment, and its cessation.

But this has to be squared with the statistic that only half of vinyl buyers actually own a turntable. Maybe this statistic is accurate, and maybe it isn't. Regardless, it brings us to the second and more important level: The experience of the object itself. A record is never just unadorned black wax — it is album art conceived with the music, stylized liner notes with lyrics, credits, and so on, and one experiences them in the same aesthetic way Dewey said we experience a painting: we approach it from a distance, we perceive the context in which the painting exists, we explore its surface and allow its various elements to become one as those elements are absorbed, and we (ideally) have some cumulative, unifying reaction throughout the process until our perception of the painting culminates.

But a record provides an additional dimension to this process. On the very basic assumption that even those listeners who don't own a turntable have at least experienced the music in another format — such as streaming — then this object is navigated with heightened sensorial interplay, in which the experience of the music and the experience of the object become inextricable from one another: one hears the album art, one reads the sound, and so on. It's through "the synesthetic interplay of the senses" that seemingly disparate elements can, in Dewey's words, "melt and fuse into unity." Like seeing the Ceźanne painting with more than one's eyes, they hear the music with more than their ears.

It should be stated outright that streaming does not necessarily disrupt all aesthetic potential, and each of us have certainly had potent musical experiences using it — in fact, the people who don't have record players and buy vinyl most certainly have. But these experiences are not what the format is after. Instead, it is optimized to be the paradigmatically anaesthetic medium in which "one thing replaces another, but does not absorb it and carry it on." The specific mechanisms by which streaming optimizes for this are obvious to any person who would make it this far in this essay. In order for this endless drift to continue (which, as has been noted, is precisely what Spotify wants), streaming necessarily needs music to become anti-tactile, heard only with the ears. It needs, as one author was recently quoted as saying in a widely circulated essay about Spotify, to essentially sit "below the threshold of listener awareness." In other words, in its most ideal form, streaming renders music into a single-sense input, with no synesthetic interplay. One cannot occupy the entirety of their sensorium with streamed music from morning to night.

Because streaming wants anaesthetic experience from its listener, it requires anaesthetic music, which requires music that embodies no experience from the musician to begin with, both in its production and its inspiration, involving non-experience at every step. Since it emerges from this non-experiential space, it becomes the musical form of McLuhan's "ditto device", whose endless, facile reproducibility is demonstrated in the 49,000 songs uploaded to the platform every day, many by fake artists, calibrated to maximize playlist placement. The natural progression to cut costs on this sonic ditto device, it goes without saying, leads to purely generative music

But there's still one last question: Why exactly do we assign greater monetary value to the thing that provides aesthetic experience?

The short answer is that this form of experience is the immutable bedrock of all there is, the fulfillment of Freud's "prehistoric wish," of Nietzsche's aesthetic phenomenon that eternally justifies existence, the irreducible goal that we're all after, the end. The long answer — well, we spent 7,000 words on

last year, which you can read some other time. Right now, we have more data to get through.All this might seem like a self-indulgent excursion away from an otherwise straightforward conclusion: if people spend more money on vinyl records, that's what artists and labels should push, regardless of the true meaning of tactility, John Dewey's philosophy, or anything else. But as we saw with NFTs, learning the wrong lessons from vinyl's resurgence can lead to disaster (and maybe make you diabolical). And as we're about to see, de-literalizing the meaning of vinyl's popularity is necessary to circumvent the format's limitations, and to make those lessons as widely applicable as possible.

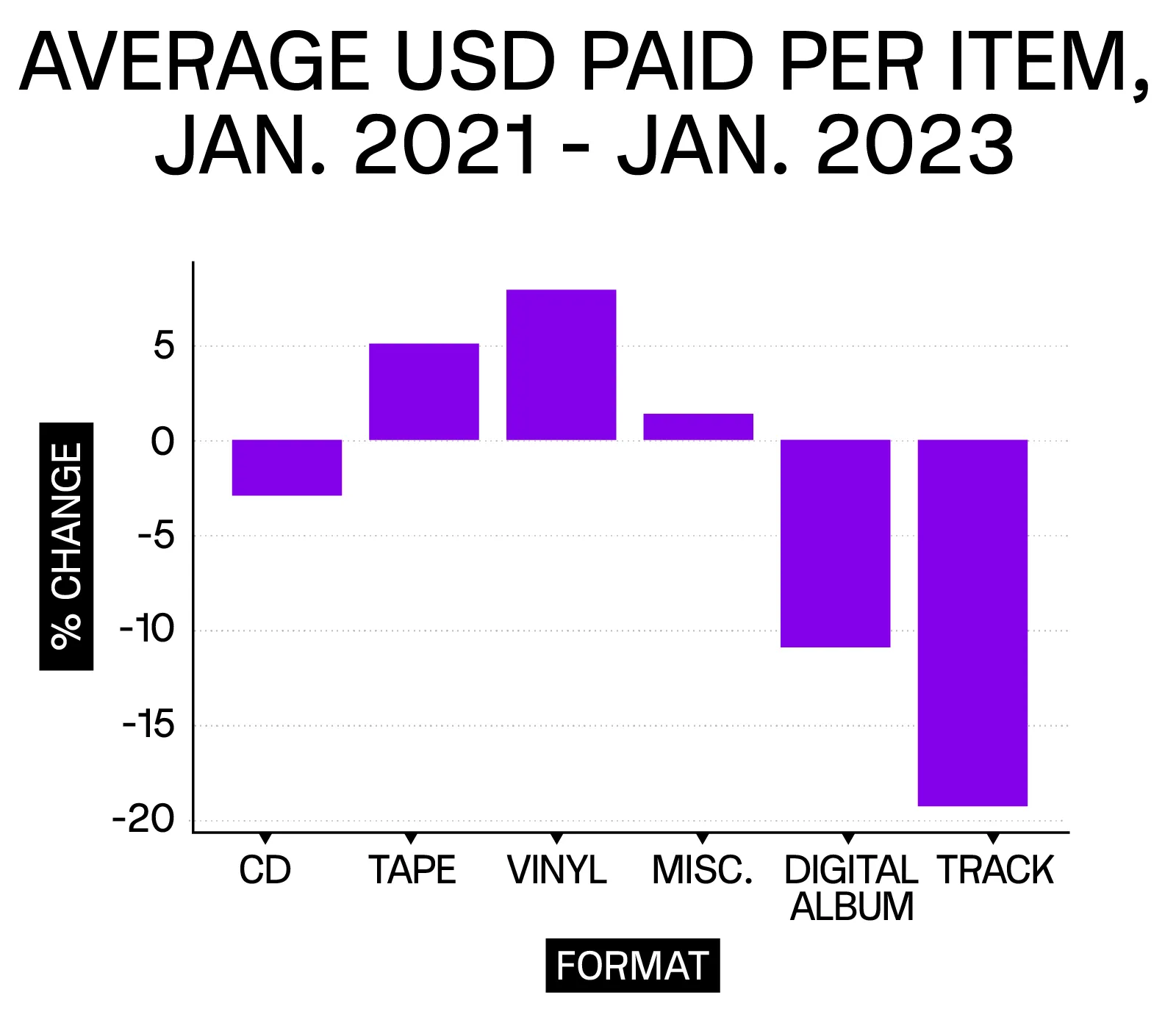

First, and perhaps most obviously to anyone trying to press an LP, producing vinyl has become more expensive. That trend appears in the average price paid for the format on Bandcamp over the past couple of years. (The change is not due to increasing generosity of buyers electing to pay more over the minimum for vinyl, a rate that has remained almost completely stable for physical goods across this time.)

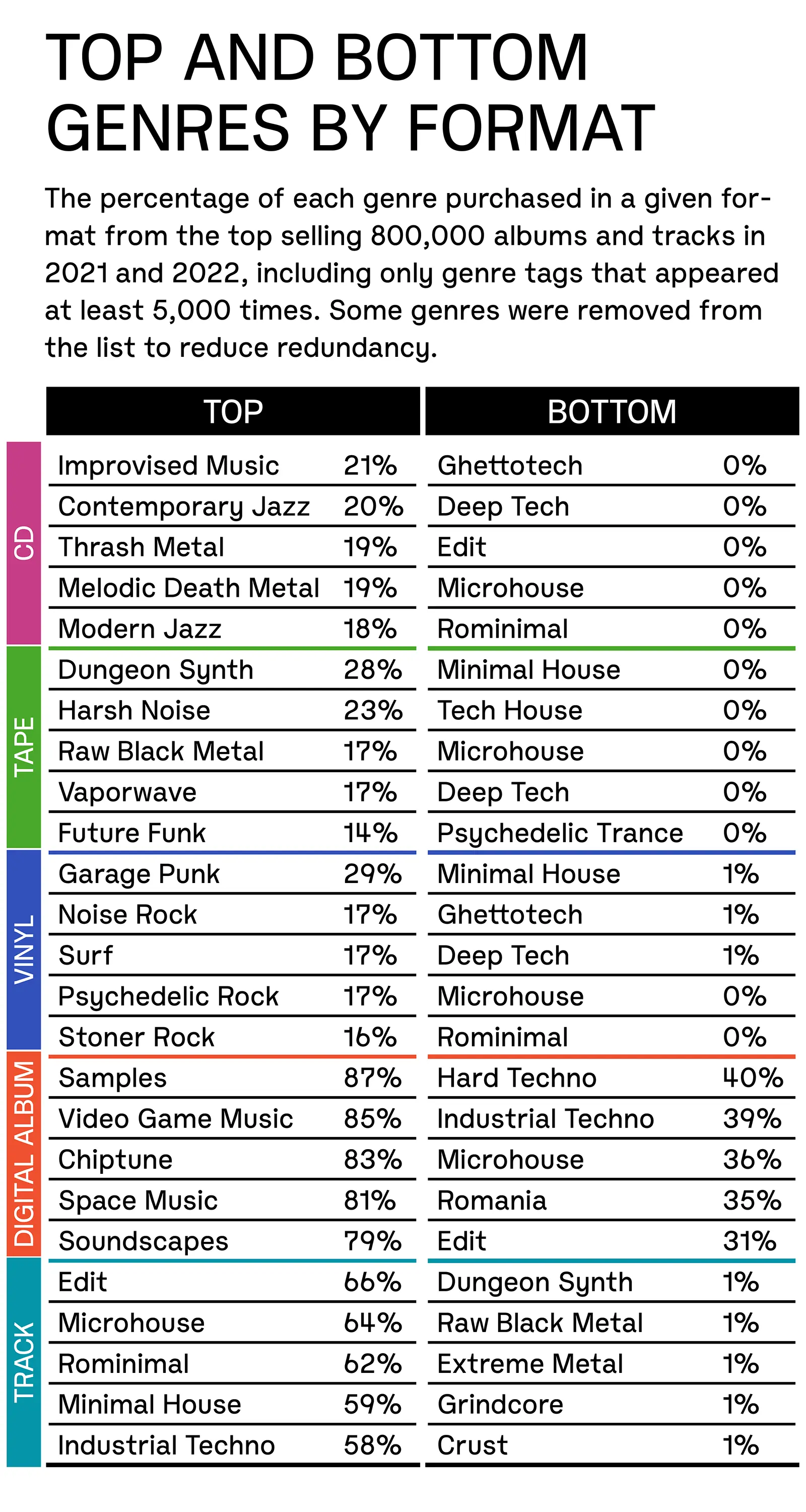

The second obstacle is that music is not format agnostic, and the ability to package different kinds of music into different formats reflects the kind of complexity that Spotify is unable to deal with in its Procrustean, one-size-fits-all platform. While vinyl has been surprisingly sellable to fans of a certain Ableton-ish sound that is engineered primarily to be streamed (Taylor Swift's Midnights being the largest example), forcing all types of music into one physical format can result in that format becoming generic and incongruent.

Third, and perhaps most interestingly, people from richer countries are more likely to buy almost every single format, including digital albums but especially vinyl, than poorer countries. The exception is for individual tracks, whose relationship between GDP is almost as inversely strong as that between GDP and vinyl.

However, the people from those countries that lean towards tracks take up a larger share of Bandcamp's customer base, which has undergone a fairly substantial shift away from the richer countries that previously provided the bulk of its buyers.

Given all this — the expense of vinyl production, the dissonance between the format and certain genres, the shifting demographics of music buyers, and the posited necessity of tactility to value in a music economy — where does this leave us with regards to re-injecting tactility into the various means of musical conveyance?

One is to simply create new kinds of physical goods or stretch the potential of existing ones. For example, CDs have maintained a staggering level of popularity in South Korea and Japan over the course of the digital revolution and vinyl resurgence, representing the largest share of music sales in both countries. K-pop labels in particular have gone further and embraced the idea that physical recordings are their own sort of merch by packaging CDs in thick, high-quality books that contain art and song lyrics, presenting the listener with much more material to pore over and providing the work with ever greater surface area. Japanese artists have bundled "CD singles and albums with perks for pop idol fans, including vouchers for priority concert ticket purchases and invitations to handshake events." The country's tight restrictions on Covid led to scaling back such events, which resulted in a consequent drop in CD sales.

There are also emerging methods that involve ways to straddle the physical and the digital. The KANO Stem Player is one interesting proposition. A palm-sized disc with an entirely haptic interface, the music player has four grooves on its surface that allow the user to independently control the stems — individual tracks for vocals, instrumentals, and so on

And then there are the attempts to bring physical performance and presence into digital space. The potential of gaming environments to foster this kind of tactility beyond that of any other electronic medium has already been embraced by musicians.

The point isn't to enumerate every possibility, but to identify that these methods are themselves innumerable. But superseding any of these consumer goods is a question of both culture and policy for how to facilitate people actually hearing other people play music, or play it themselves, in the flesh, the foundation for how we perceive music in any format. The musician Jaime Brooks summarized this importance in an interview earlier this year:

When I was in my, like, early 20s, in Minneapolis I posted things on Craigslist about wanting to start a band…And it worked! I met people that way…I was out experiencing music with people every weekend. There was this big, open, weird, chaotic possibility space that I felt like I could tap into…And it was a communal experience…I think everyone should be able to access some version of that...I think that if people were just doing it more in-the-room together, if that wasn't so difficult and expensive to make happen. If people were doing that part of the process in school consistently, before being turned loose onto social media as an aspiring teenage producer or artist or whatever, I think it would be better…I think the rent issue is the biggest thing keeping that from happening. It's just too hard to physically get space for people to be doing this, and still be able to make money off of it.

Nothing we can write about here is a solution for macroeconomic problems, none of them will make housing and other space affordable, none of them will keep the possibility of medical bankruptcy at bay, and none of them are able to replace the significance of fumbling around trying to place a bass or a saxophone or a drum machine when you're 15, and being in a room and listening to those who actually can.

But if the ways to foster tactility and experience are innumerable, so are the ways not to. We'll mention just one: As with everything else, it comes courtesy of Spotify, in its recent attempt to create a pseudo-TikTok homepage in which 10-second clips of music videos play on repeat during truncated "preview" clips of a song.

Of all the innumerable examples, this one matters for the same reason Steve Jobs's promise that you could touch your music does: It acknowledges on some level that tactility, that "fruitful meeting of the senses, of sight translated into sound and sound into movement, and taste and smell," is a phenomenon of paramount significance. And like Jobs, it hasn't the slightest idea what that actually means.

Throughout the research and writing of this project, a scene from Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides continuously presented itself as a mental banner under which the report was completed. In the scene, the 17-year-old ingenue Lux Lisbon has sex with the heartthrob quarterback Trip Fontaine on the school's football field while the rest of the school is at the homecoming dance. Abandoned by Trip afterwards, she spends the night sleeping on the field, breaking the curfew imposed by her mother that was a nonnegotiable condition for her and her sisters to go out, and instigating a crackdown that permanently confines all the girls to their home. In the film's most wrenching scene, Lux's mother punishes her by forcing her to burn her records. Lux sobs with the abandon of any separation trauma as she forces herself to drag them down the staircase and throw them into the fire, pleading to not have to burn her Aerosmith LP, until the house fills with smoke and her mother, a stoic midwestern tyrant, tosses the crate's unburned remainder into the garbage bin.

The duality between the paradigms of experience and non-experience, and the sets of antithetical goods they produce, has preoccupied Components since 2020.

produces Scorsese, the other viewer-optimized binge content. produces Pikmin, the other Monday.com.December 16, 2020

The Map and the Category

Mapping the genre tags of 1 million items on Bandcamp

So instead we'll just say this: Love — of a place, a person, an LP, Pikmin — doesn't take place outside the framework of experience. It is tactile, and it is aesthetic. That Silicon Valley has provided us with the anaesthetic and non-tactile is why it so often leaves us with nothing to care about much at all. And it's why it has so much trouble working out the kinks of getting us to pay for it.

Thanks to Jameson Orvis and Heather Mease for their help throughout this project.